OUR ANCESTORS, THE BUGUOIS

FROM GAUL TO THE YEAR 1000

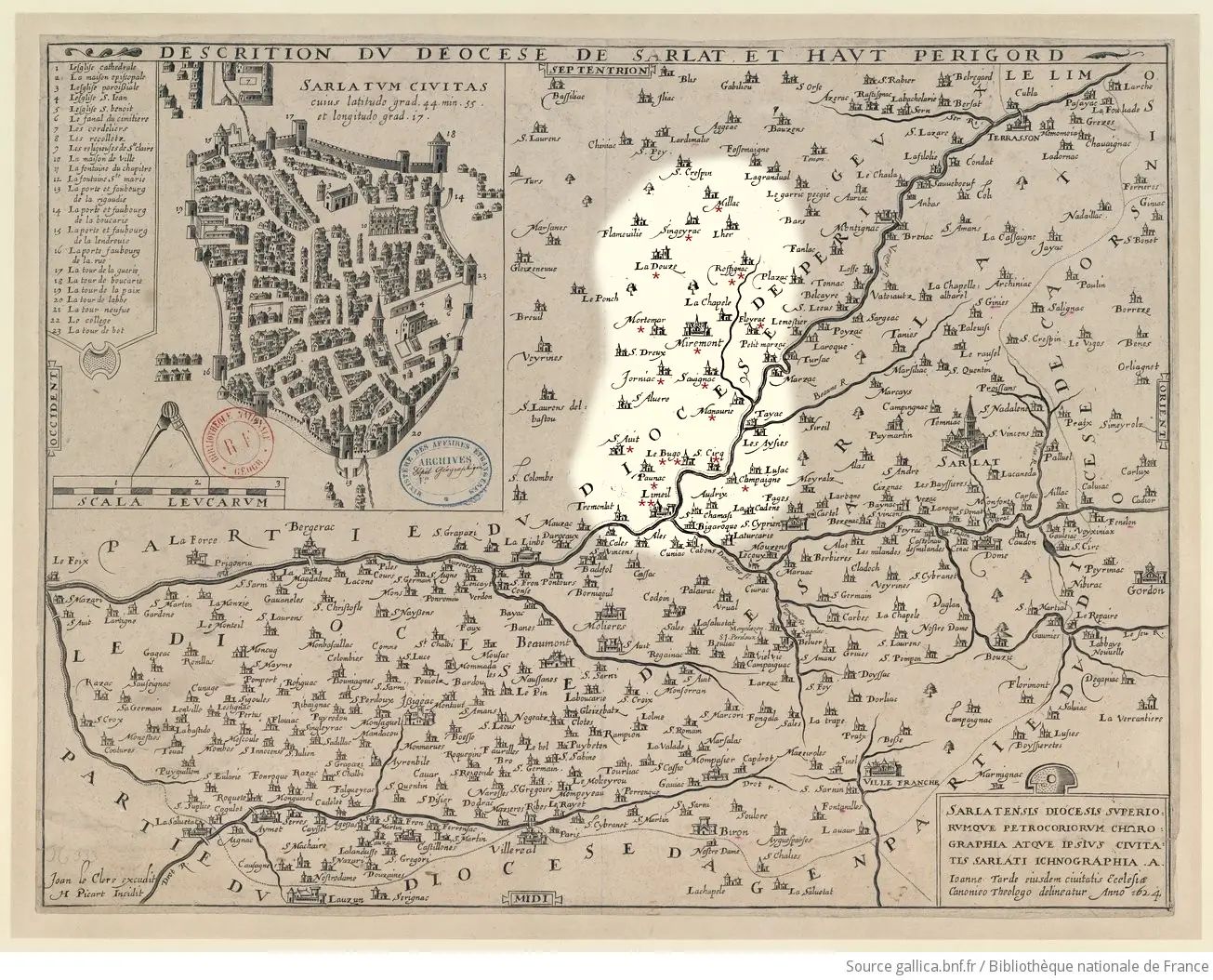

A brief look back at a significant area of influence, of which Le Bugue — at the heart of the Black Périgord — remains the beating heart.

by Sophie Cattoire

It was the time of Abbeys and their Mills – An example with the Frankish hundred of Albuca, which saw the birth in the year 1000 of the convent of Dame Adélaïde, at the crossroads of the Ladouch stream and the Vézère river.

Summary:

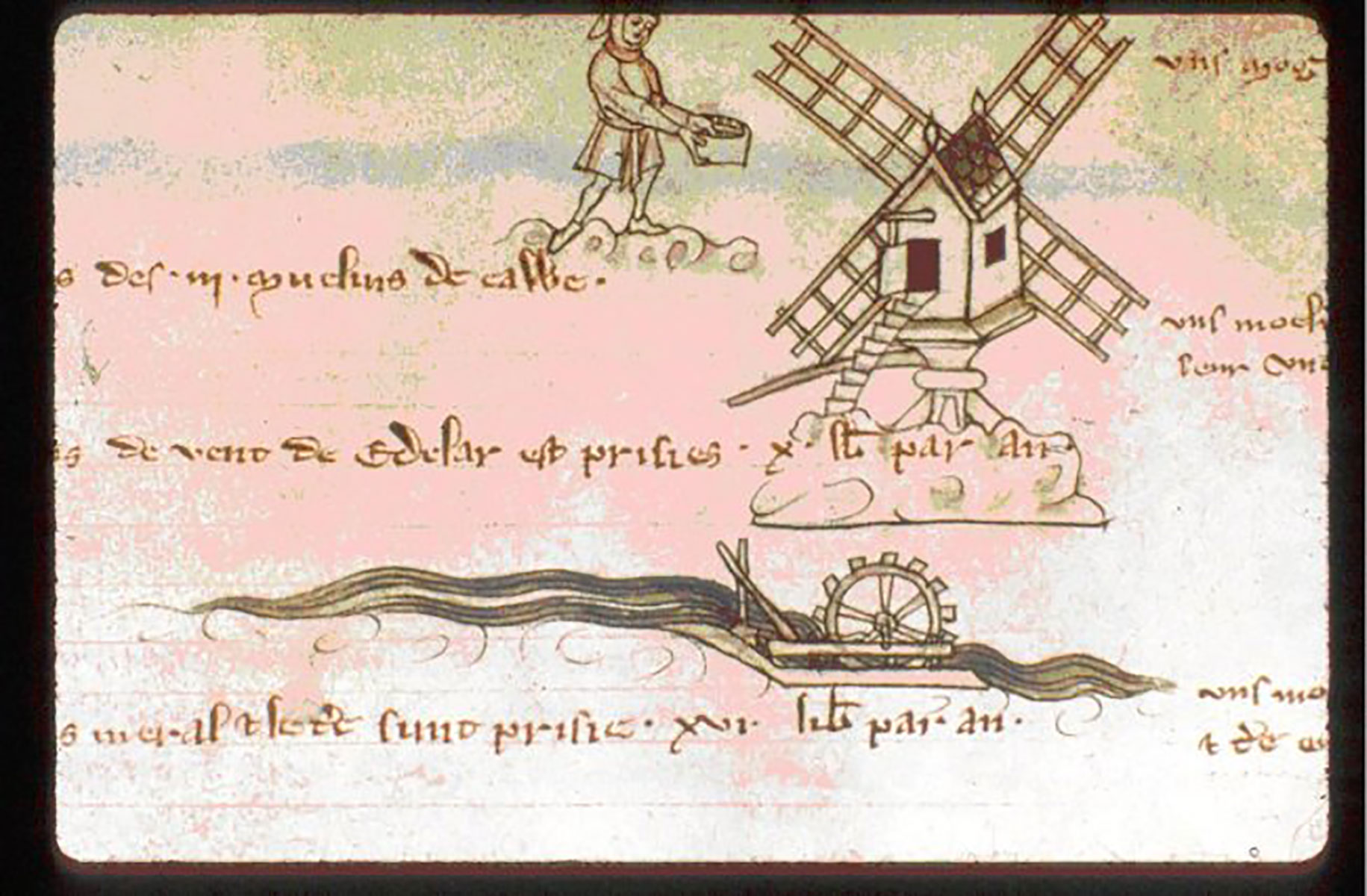

In the middle of the Middle Ages, there was a major energy transition that deeply transformed society. We invite you to grasp the extent of this transformation through the example of the development of a group of villages, then medieval parishes of Périgord. They were all under the leadership of Albuca and were all caught up from the year 1000 in the rapid emergence of abbeys and their mills.

There was indeed a timely encounter, a prodigious collision, at the origin of a progressive revolution in techniques and customs. After the first dynasty of the Frankish Kings, that of the Merovingians, pagan Germanic barbarians who became Christians to survive, it was necessary to wait for the Carolingian Renaissance for the Catholic Church to truly acquire a central place in medieval society.

This surge of piety was accompanied by numerous donations of real estate, including farms and their mills, from wealthy members of the knighthood. They hoped to ensure the salvation of their souls through the purchase of "indulgences," which in this case translated into donations of part of their heritage. And it was precisely at this moment that the mastery of hydraulic power, through the mills, would put an end to slavery, inherited from Roman law and still shamelessly practiced by the Merovingians.

This renewable energy would replace the force of slaves and animal traction. Medieval society would replace the forced manual labor of men and beasts with the continuous rotation of mill wheels day and night.

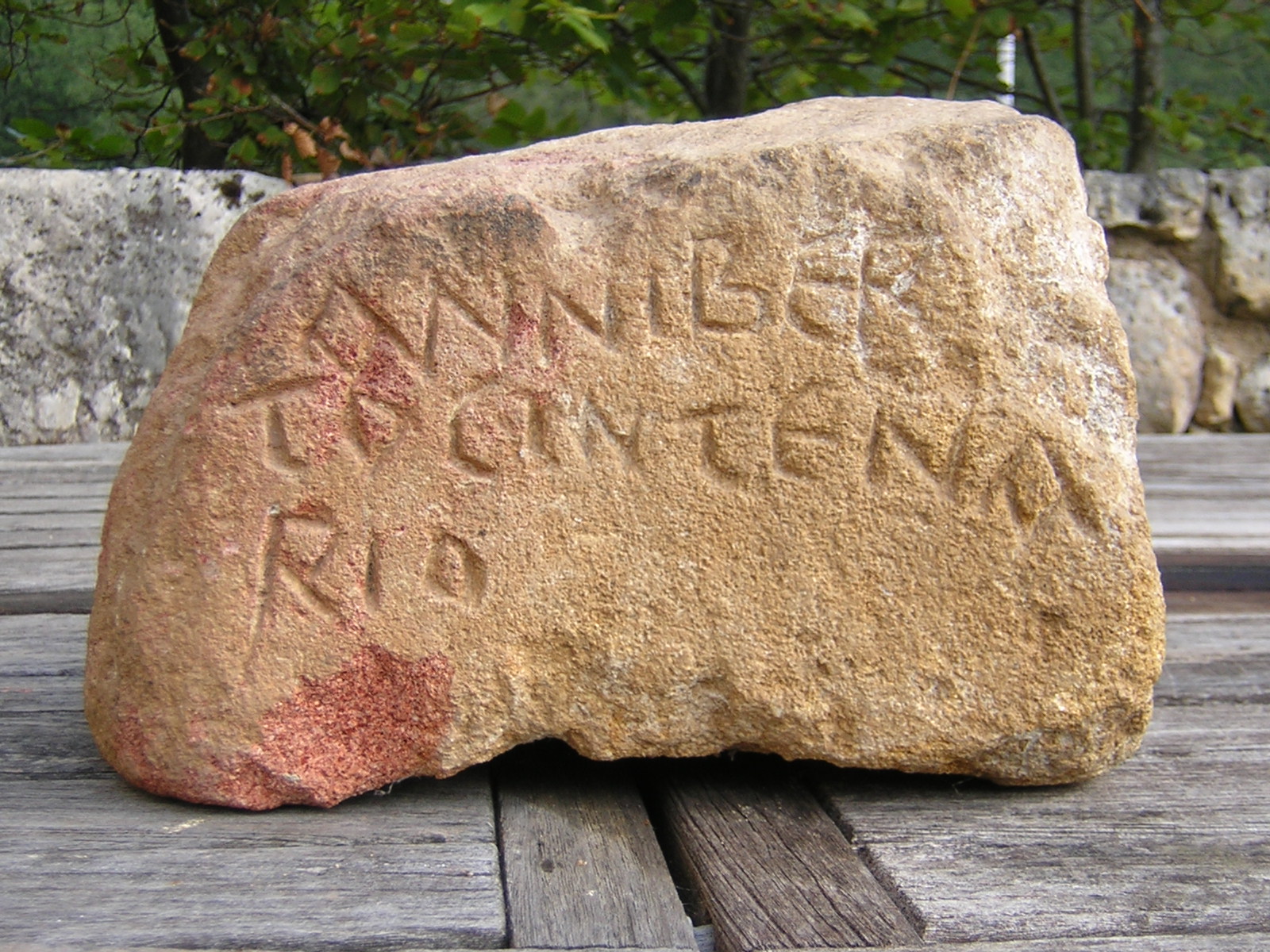

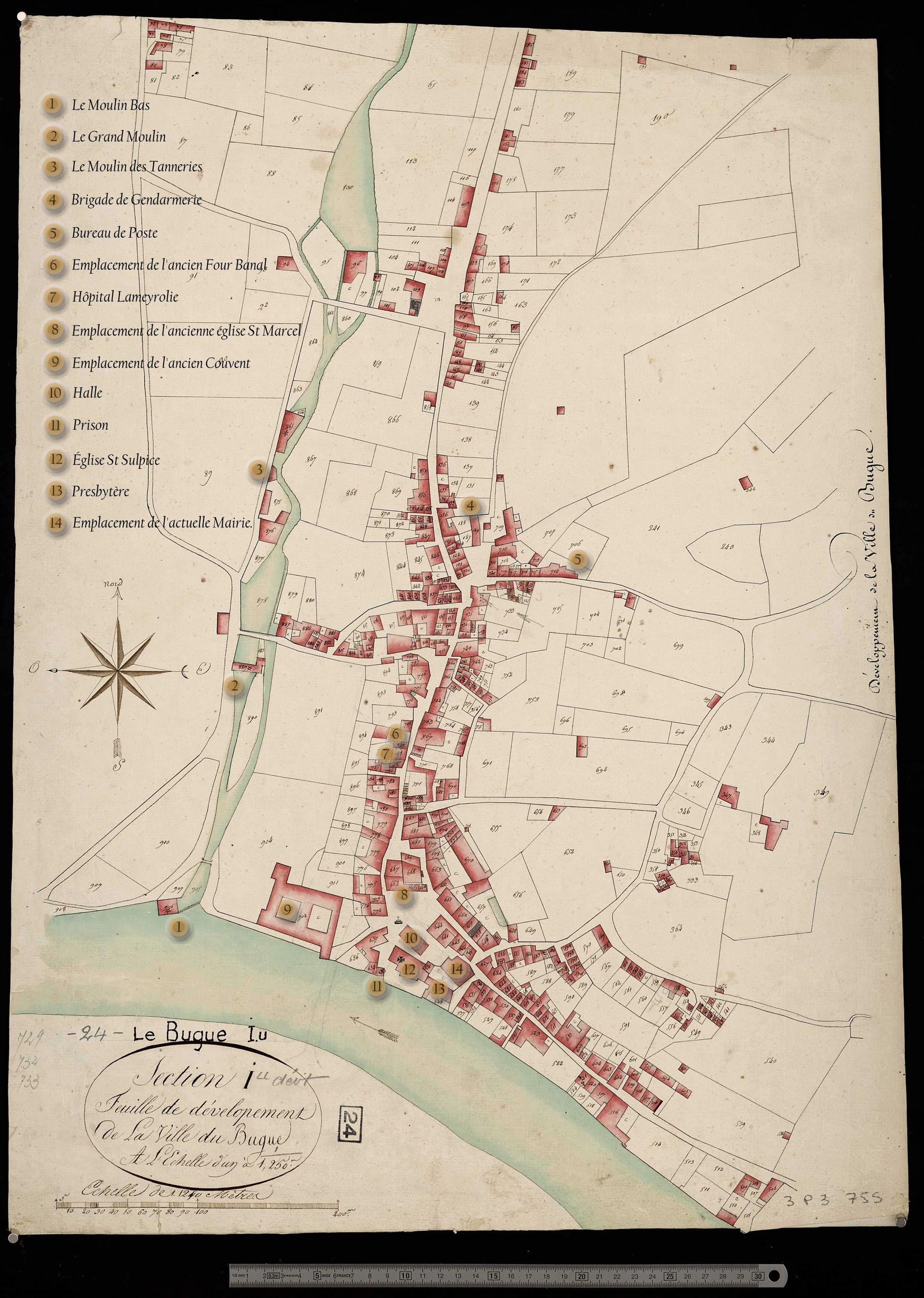

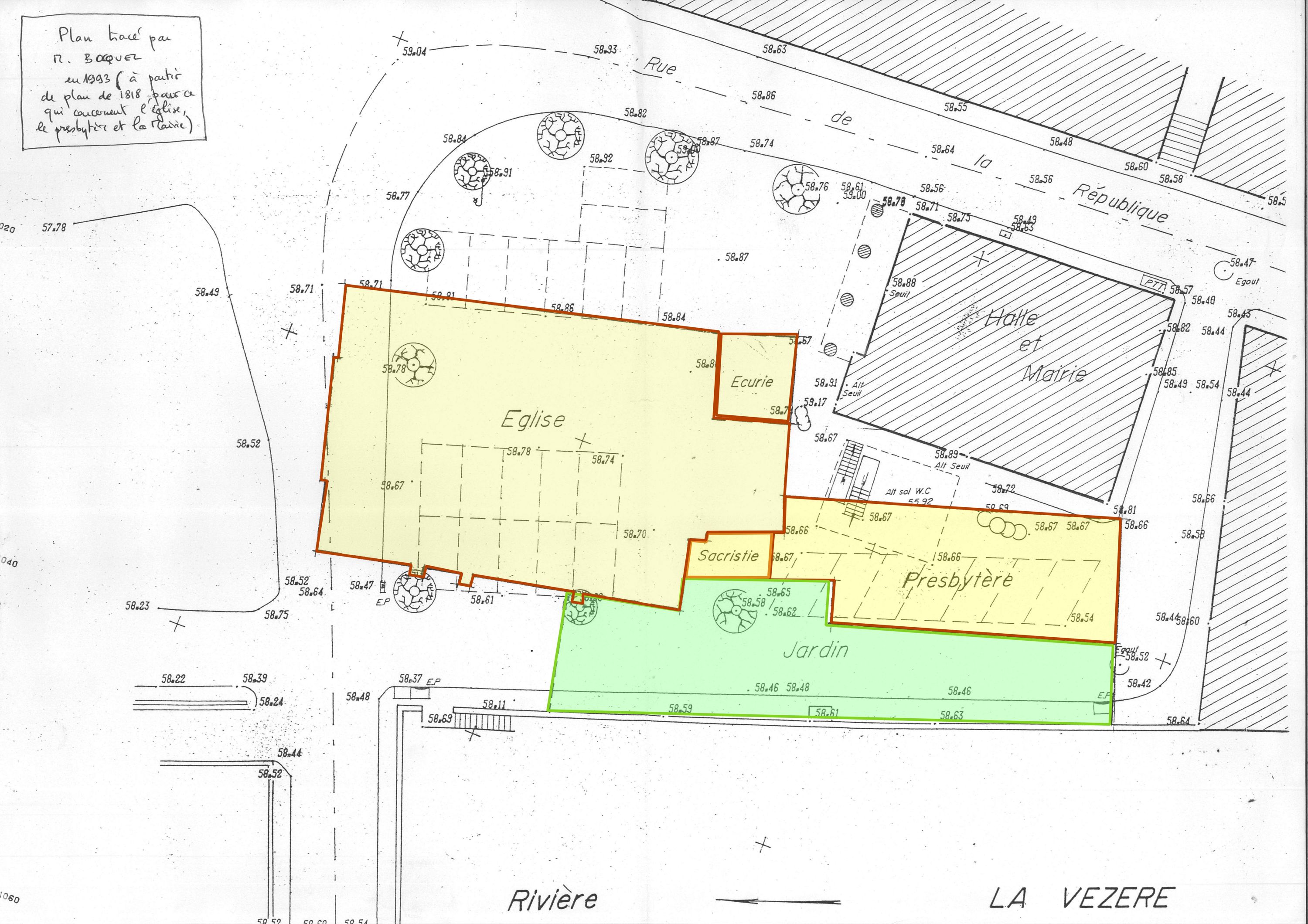

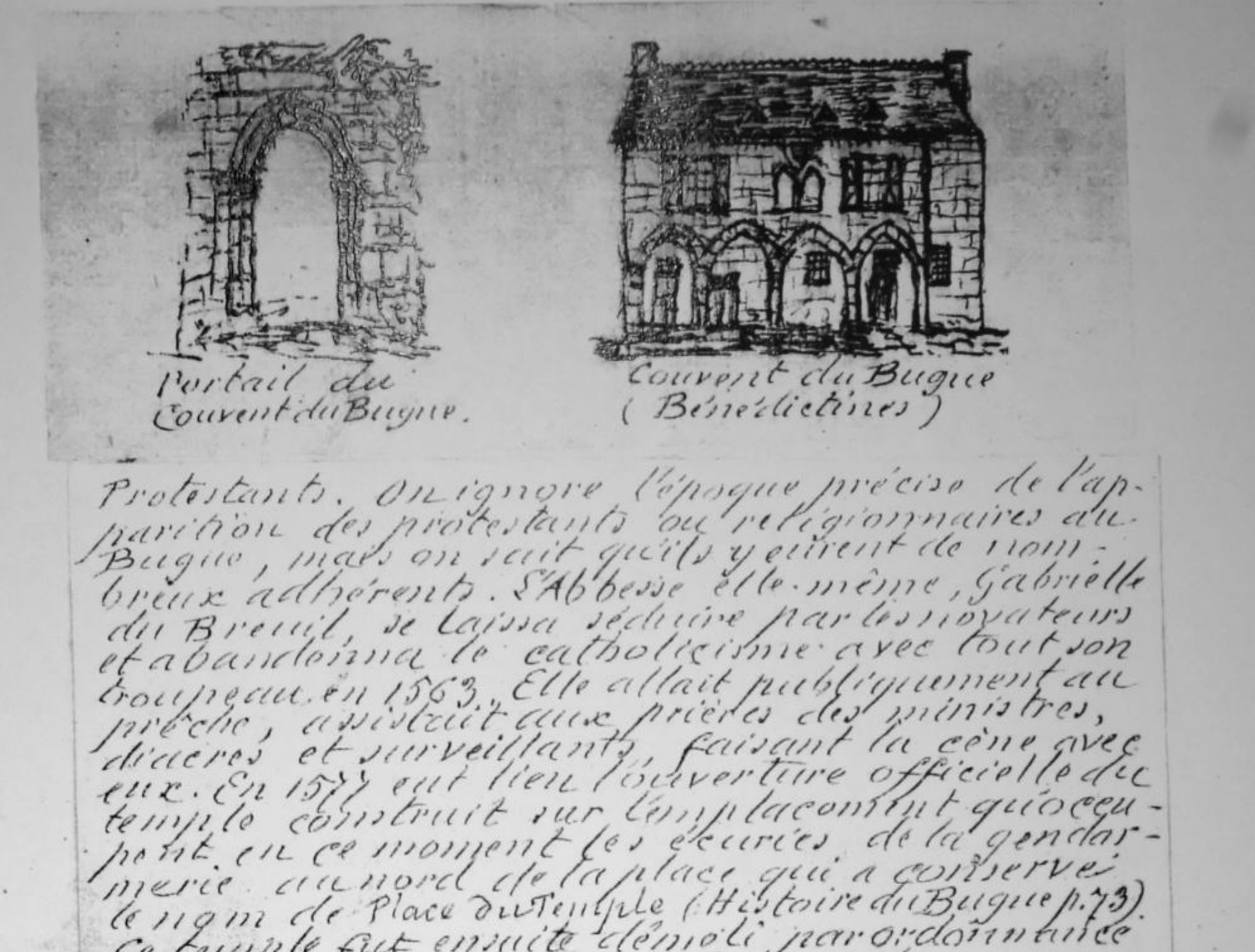

This transformation was fully experienced by the archpriesthood of Albuca, the oldest in Dordogne, where the convent of Benedictines of Dame Adélaïde was established in the year 1000. Albuca, its Gaulish name, then became Albuga, its Occitan name, and ultimately Le Bugue, its French name that we know today. In present-day Bugue, one can still find some traces of this flourishing past.

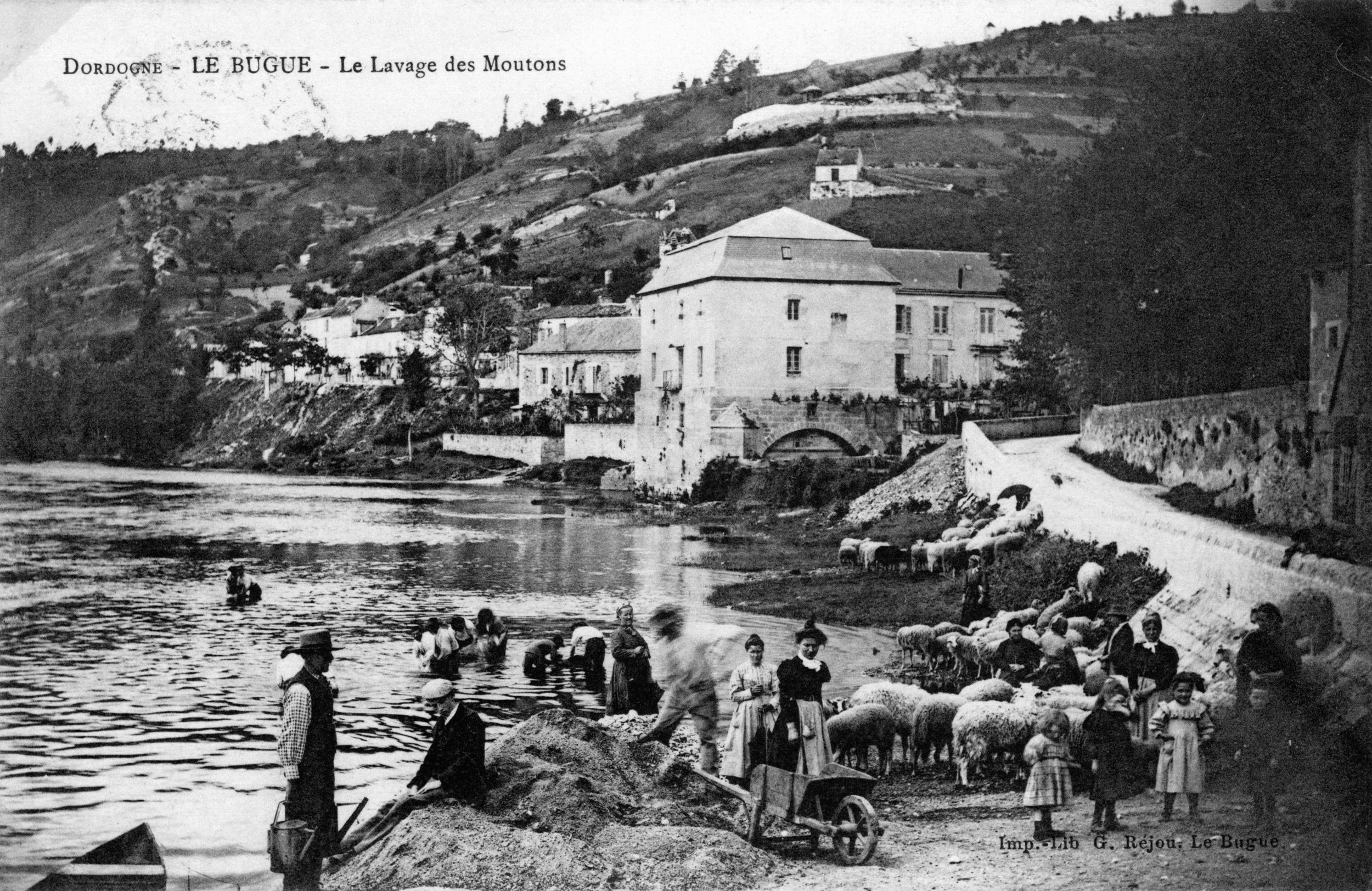

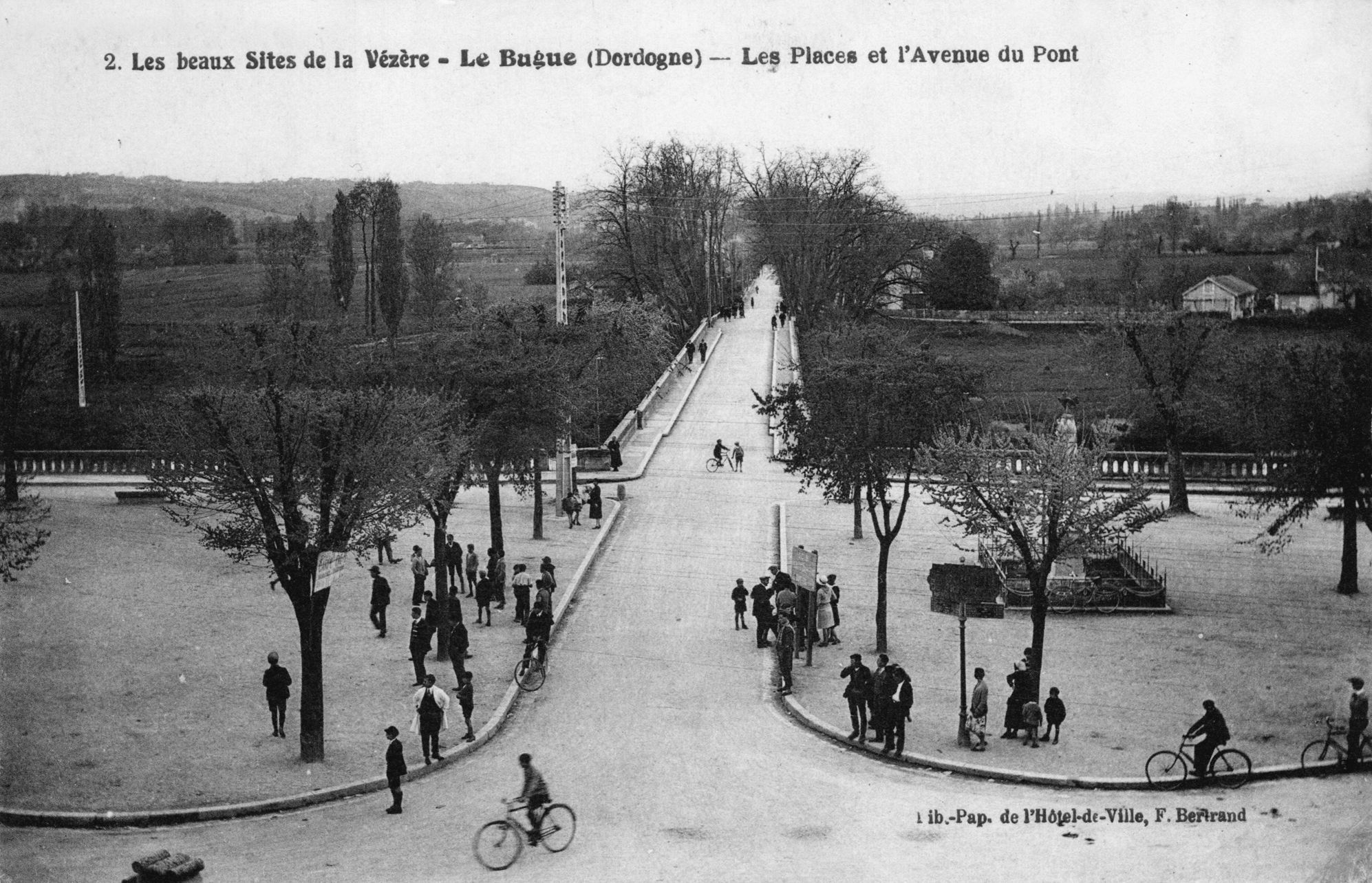

On the edge of the clear Ladouch stream that crosses the village before flowing into the Vézère river, the Moulin de La Barde has preserved its medieval castle-like architecture. It contributed to every mission entrusted to mills since the Middle Ages until the Industrial Revolution. Daily bread, oil for lighting homes, leather, sheets, woolens, ropes, and finally electric power to supply the entire village of Le Bugue thanks to its turbines, it has given everything in turn and remains standing to testify.

A look back at this forgotten medieval revolution with the example of Albuca, a Frankish hundred that became Albuga in Occitan, and then Le Bugue, inheritor of this past that still holds its charm and continues to enjoy powerful attractiveness.

ONCE UPON A TIME, ALBUCA...

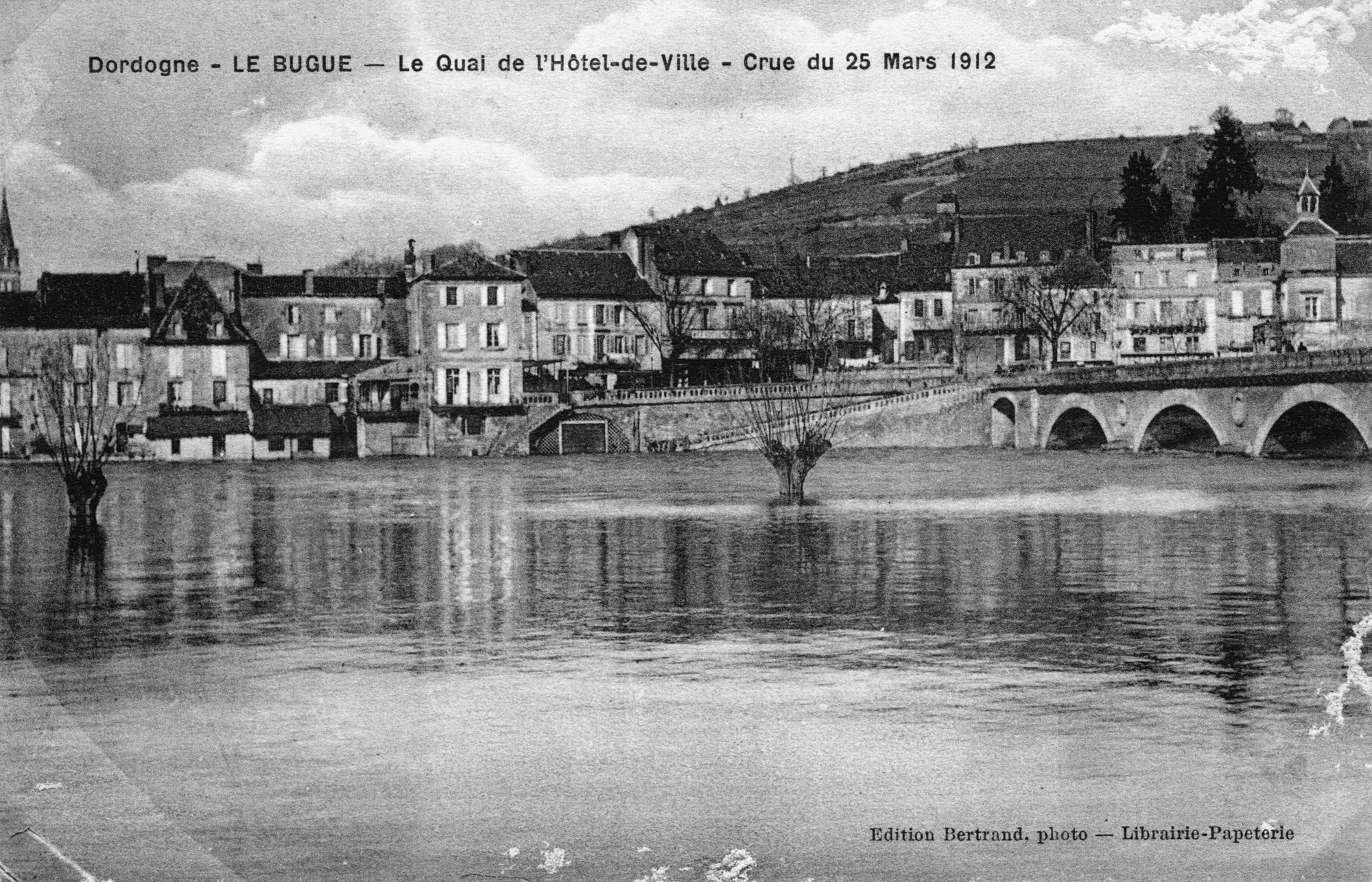

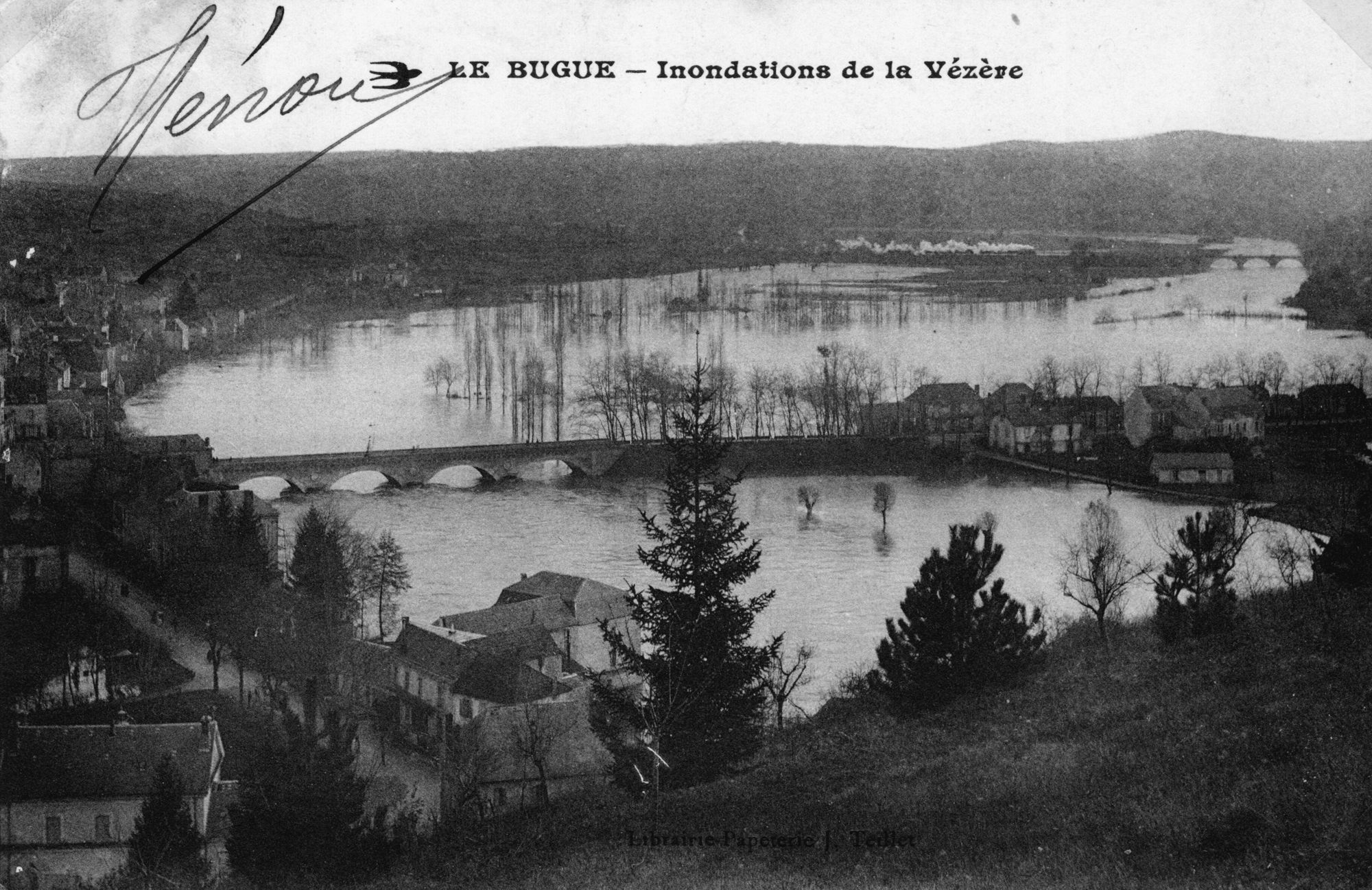

The choice of landscapes to settle in after the nomadic Prehistory, 10,000 years ago, is characterized by mature and wise thinking. The lively waters of the Ladouch stream — "The Source" in Occitan — splash the hillsides of a fertile valley before flowing into the Vézère River. It floods, in turn, vast undulating plains through its sinuous meanders.