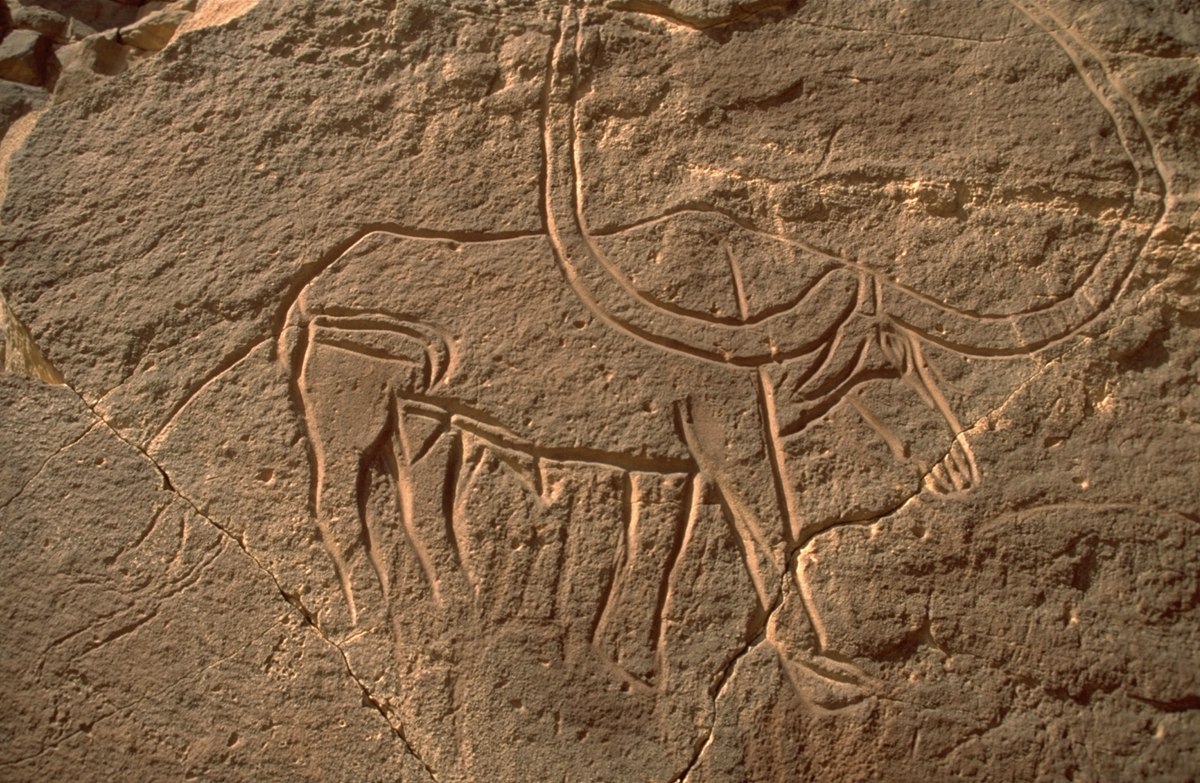

THE ROCK ART OF TASSILI N'AJJER

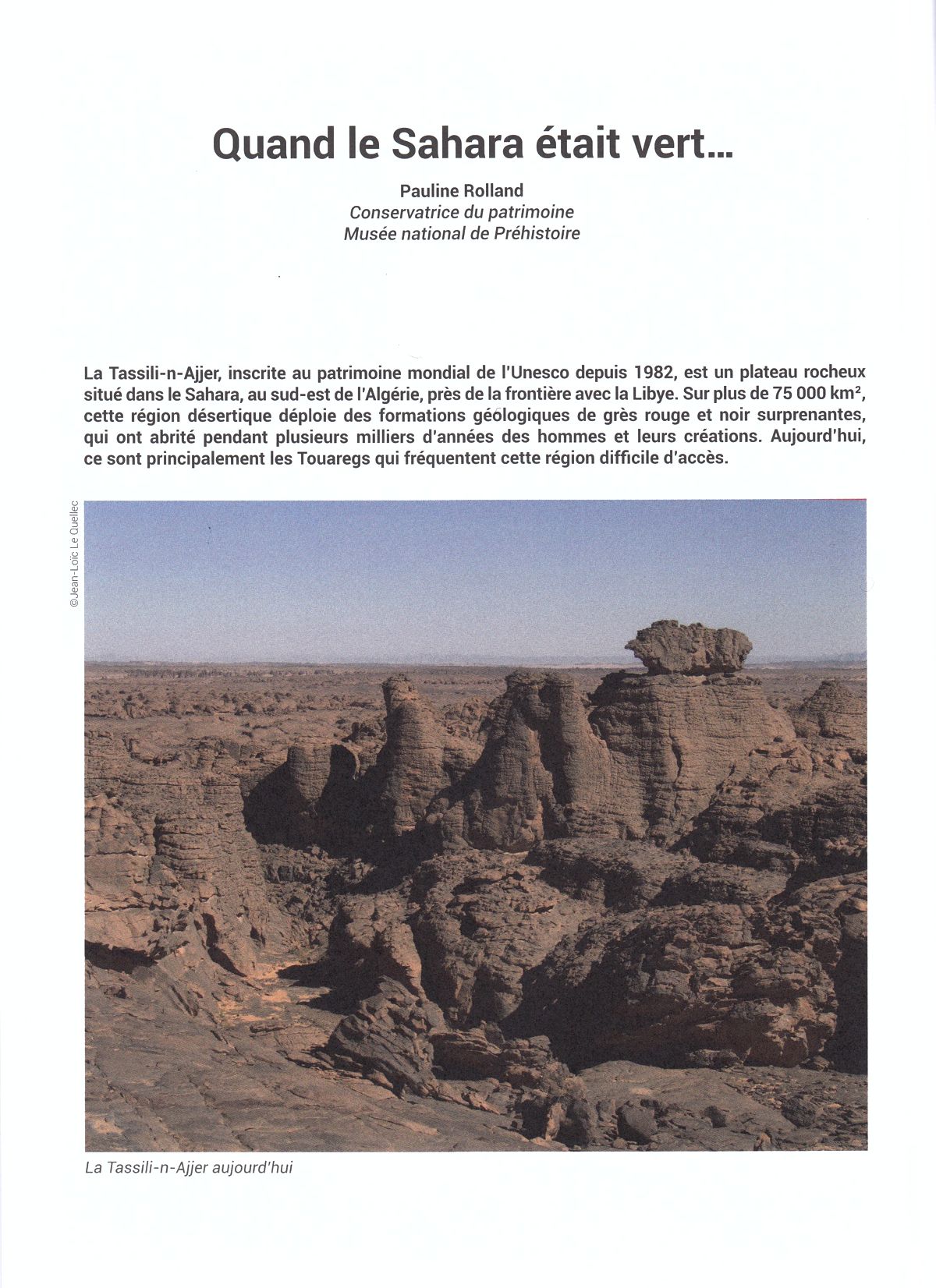

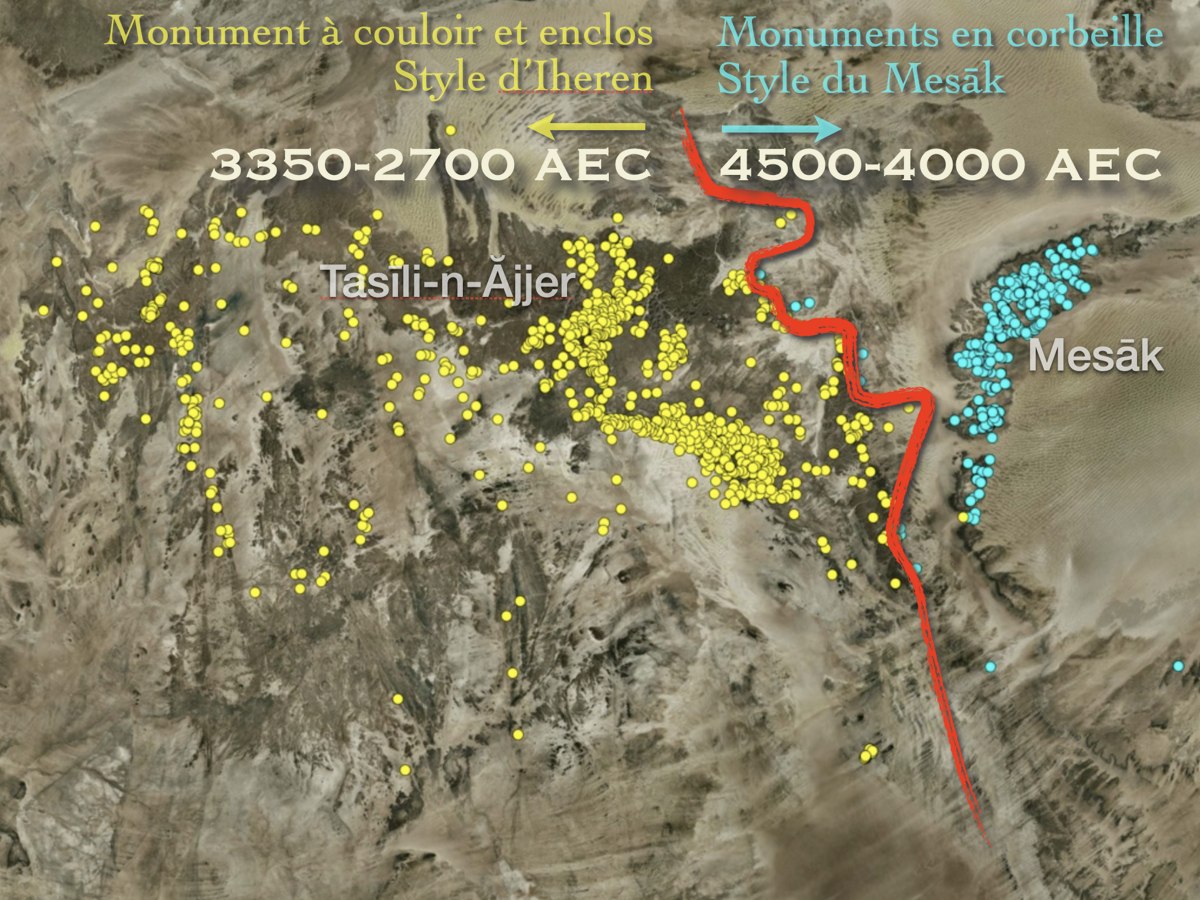

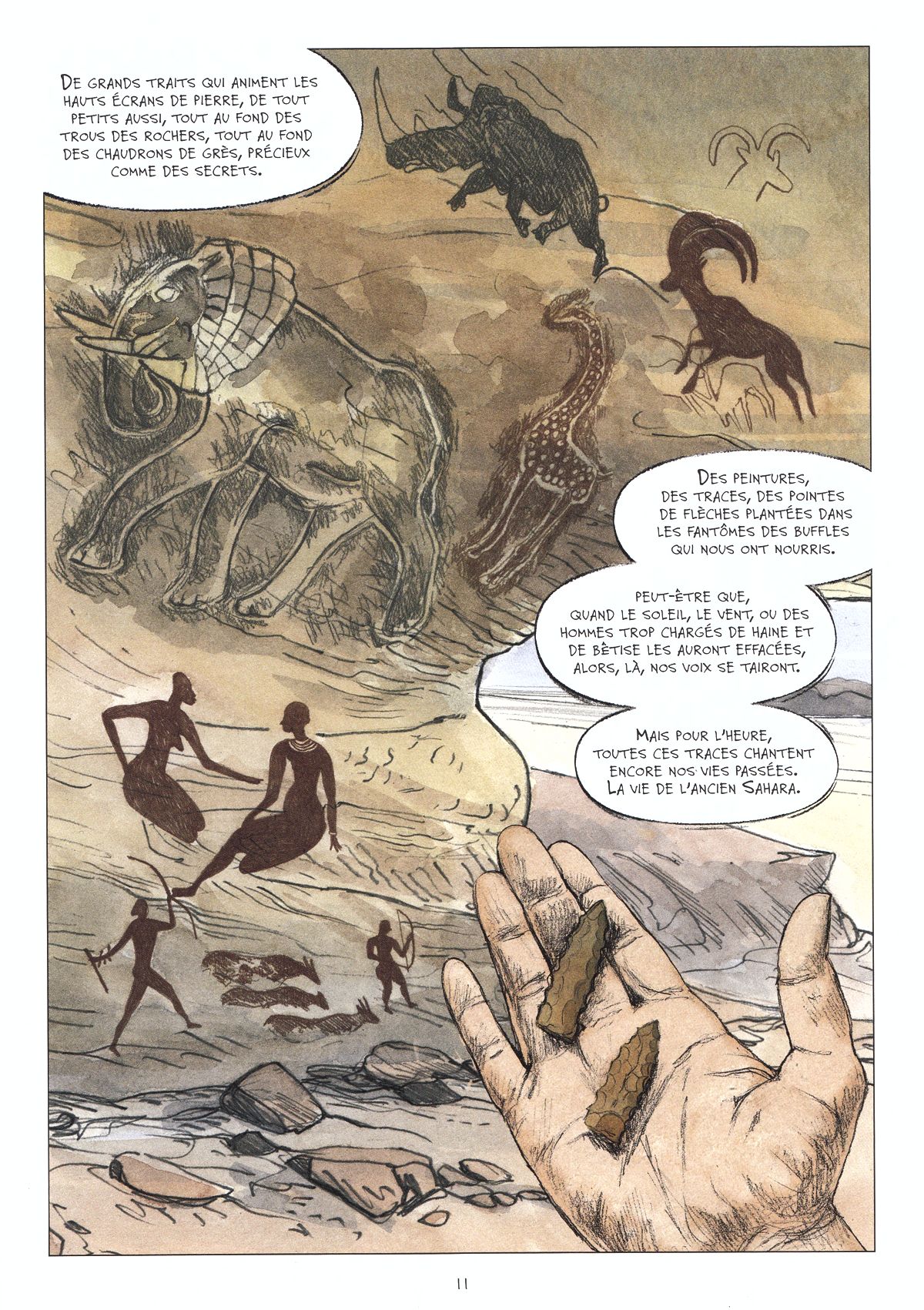

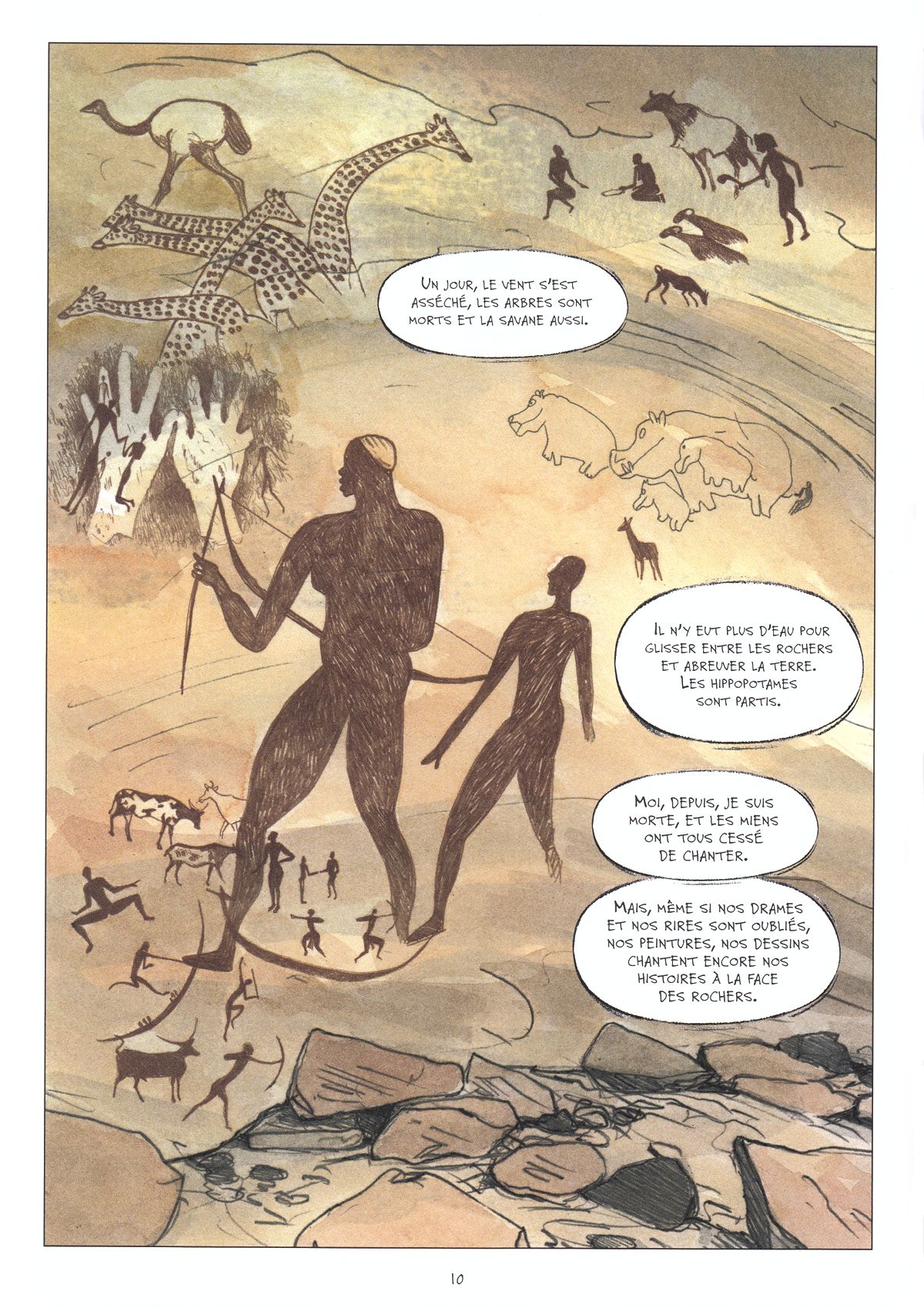

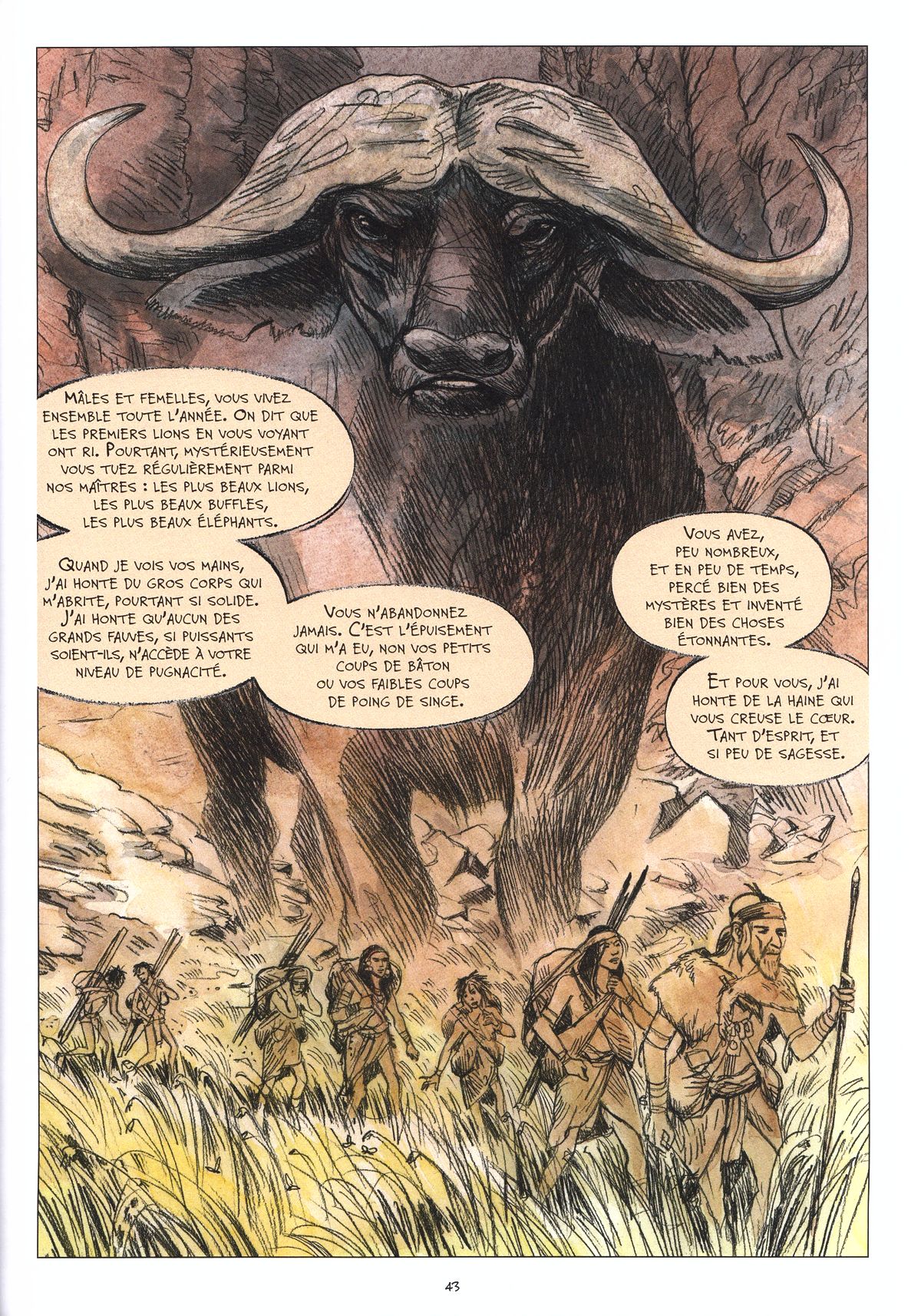

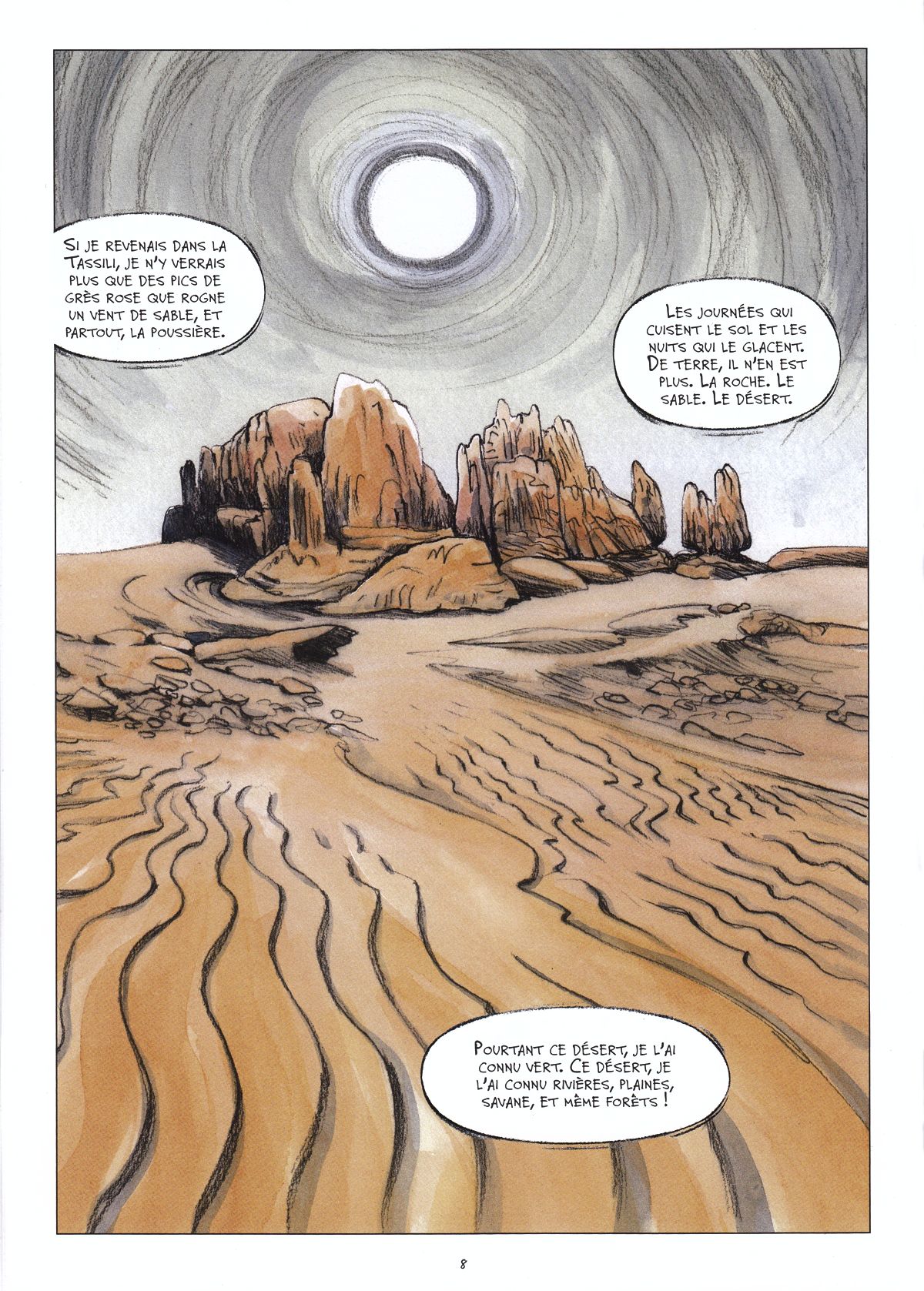

Life in a green and fertile Sahara swept away by the advancing desert 7,000 years ago

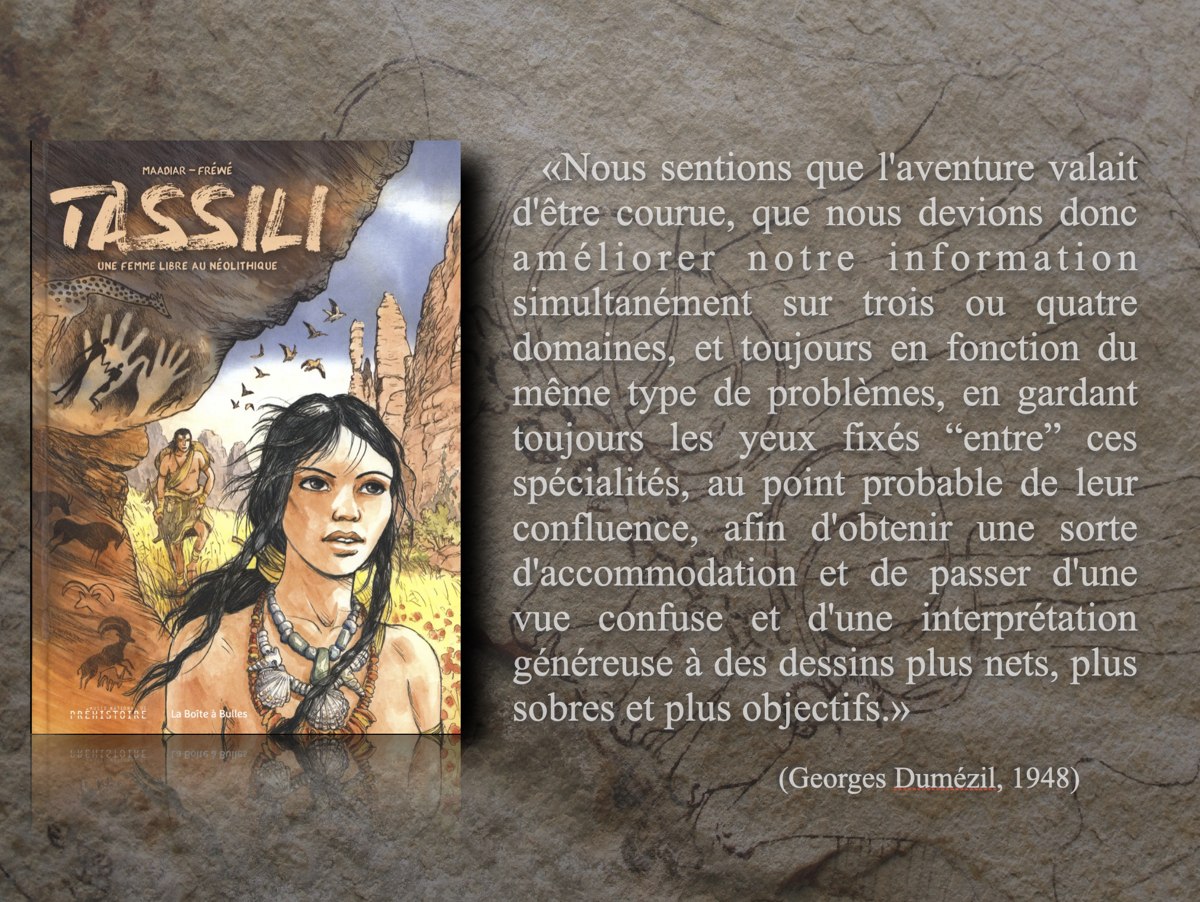

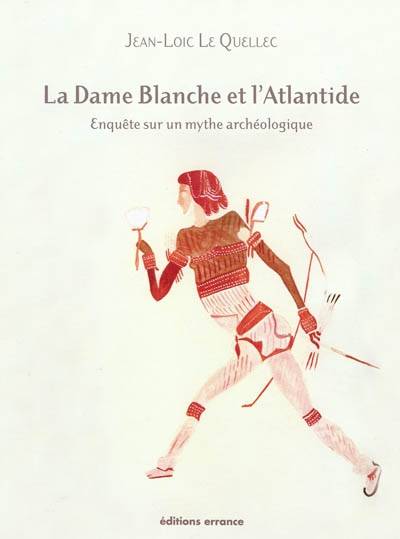

Arguably, the romantic desire to discover The Lost Land of Atlantis beneath the sands of the Sahara led the first discoverers to lean towards mythology rather than scientific research, blending imaginary tales and genuine discoveries, but it is however possible to associate research into our past and the artistic expression of our contemporaries without confusion. A borderline can be clearly defined between these two fields. With this in mind, the team at the Musée National de Préhistoire wanted to couple a scientific conference with the “avant-première” release of a comic book.

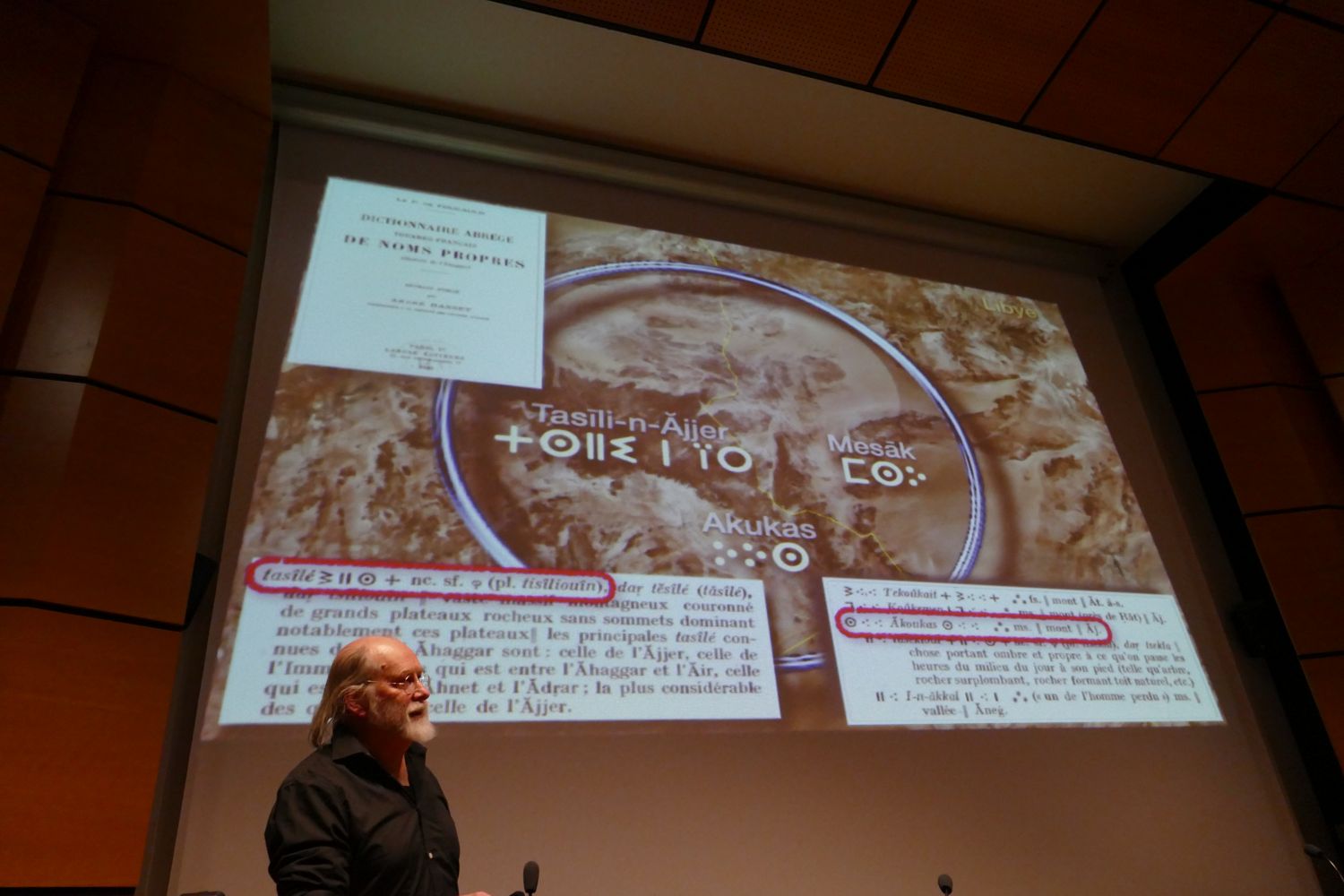

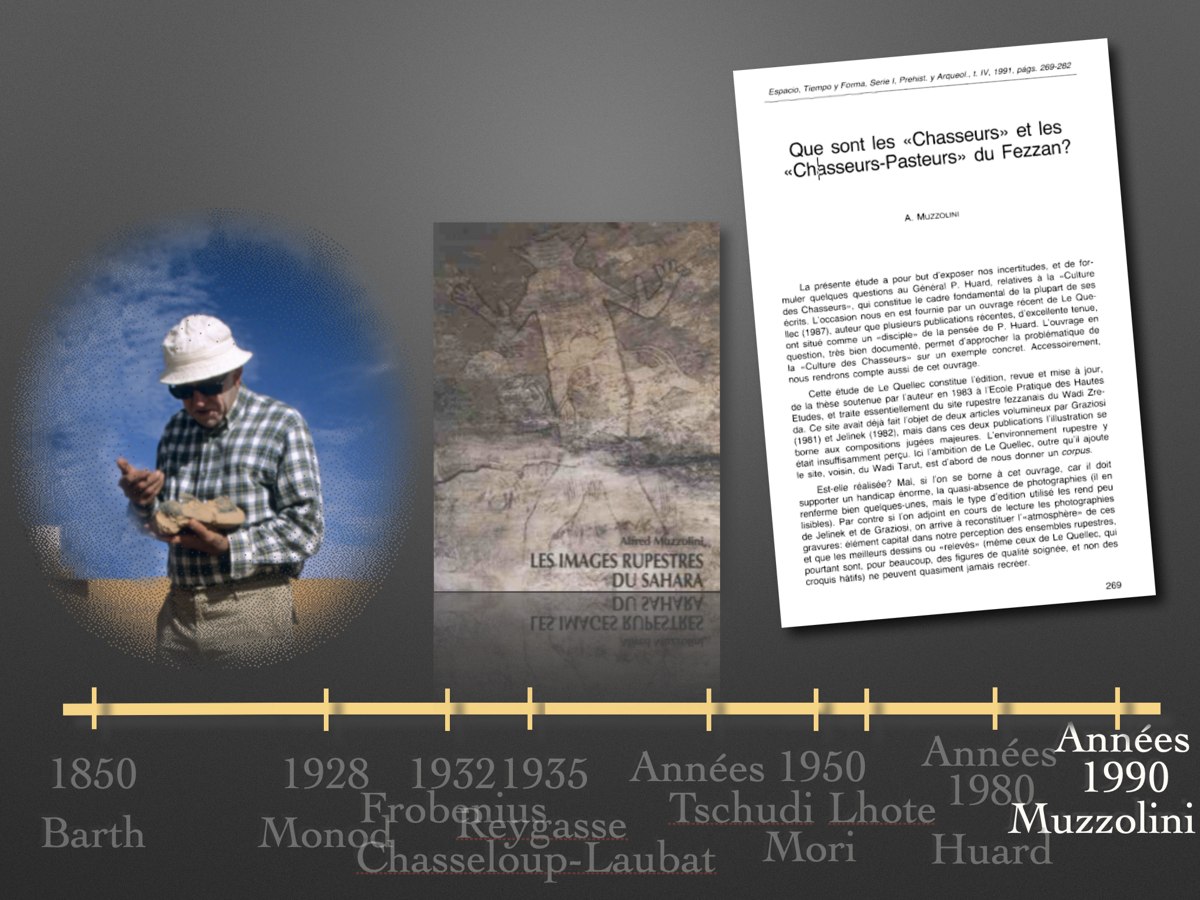

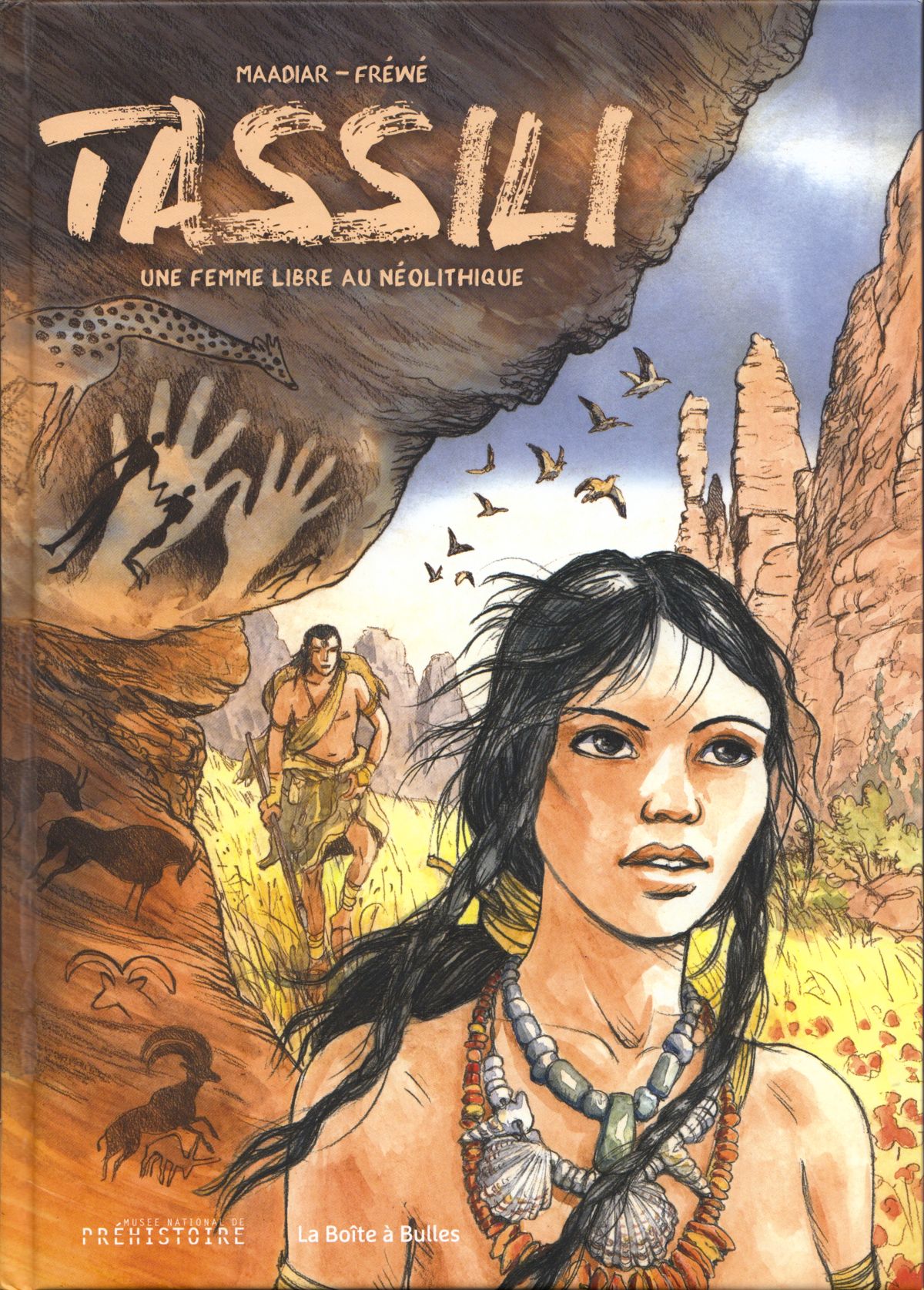

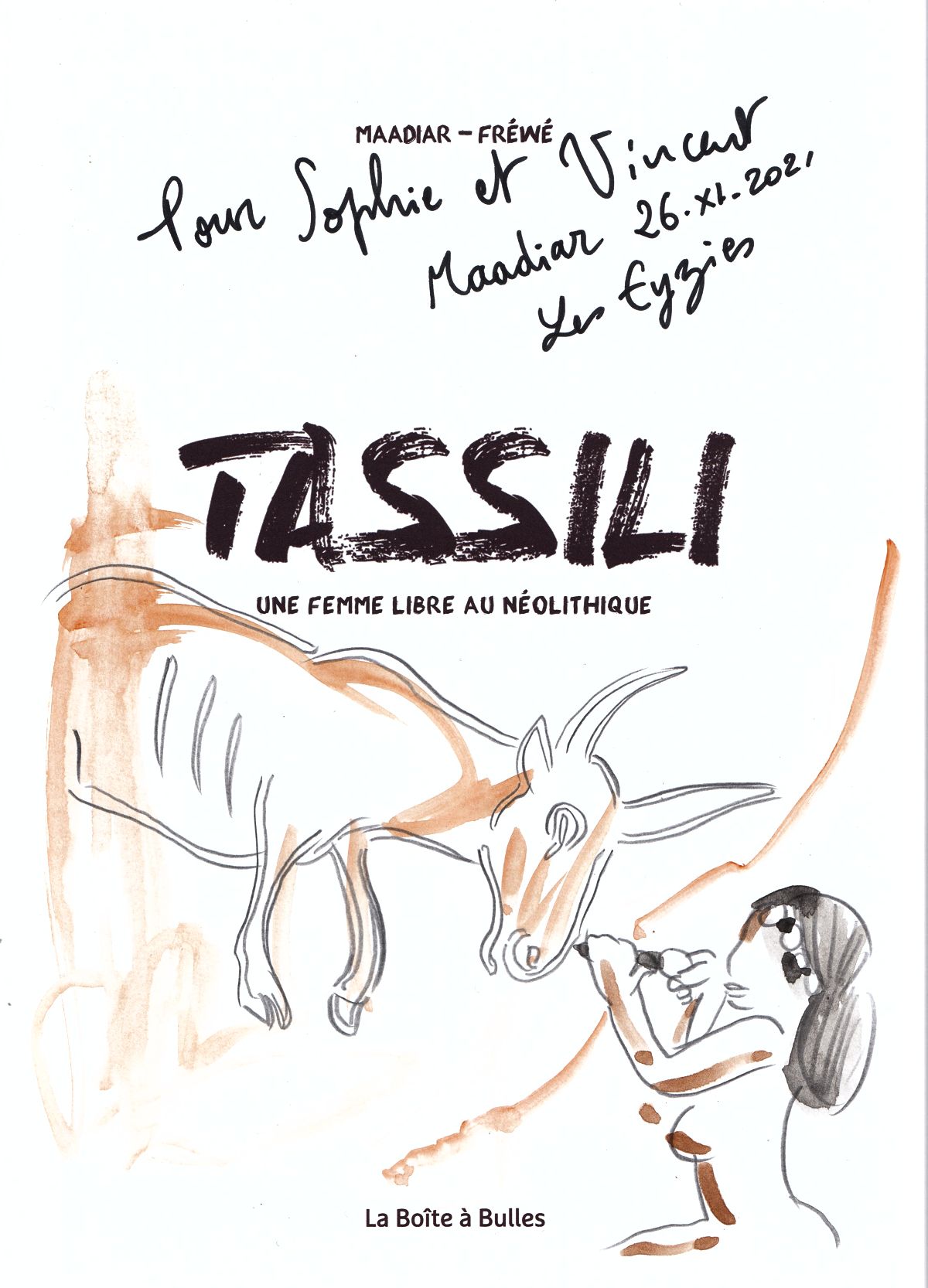

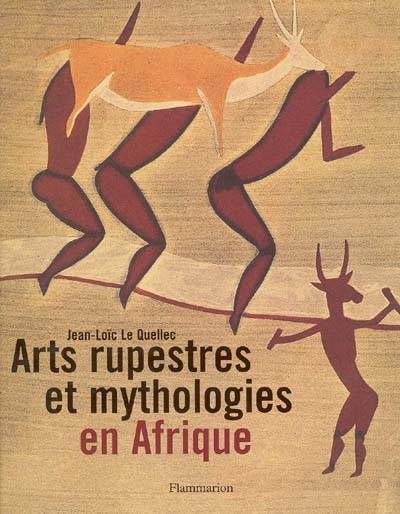

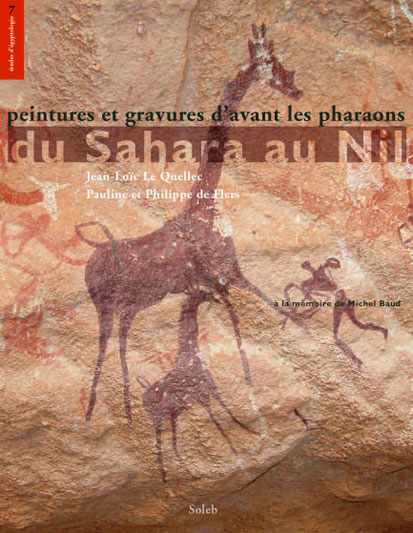

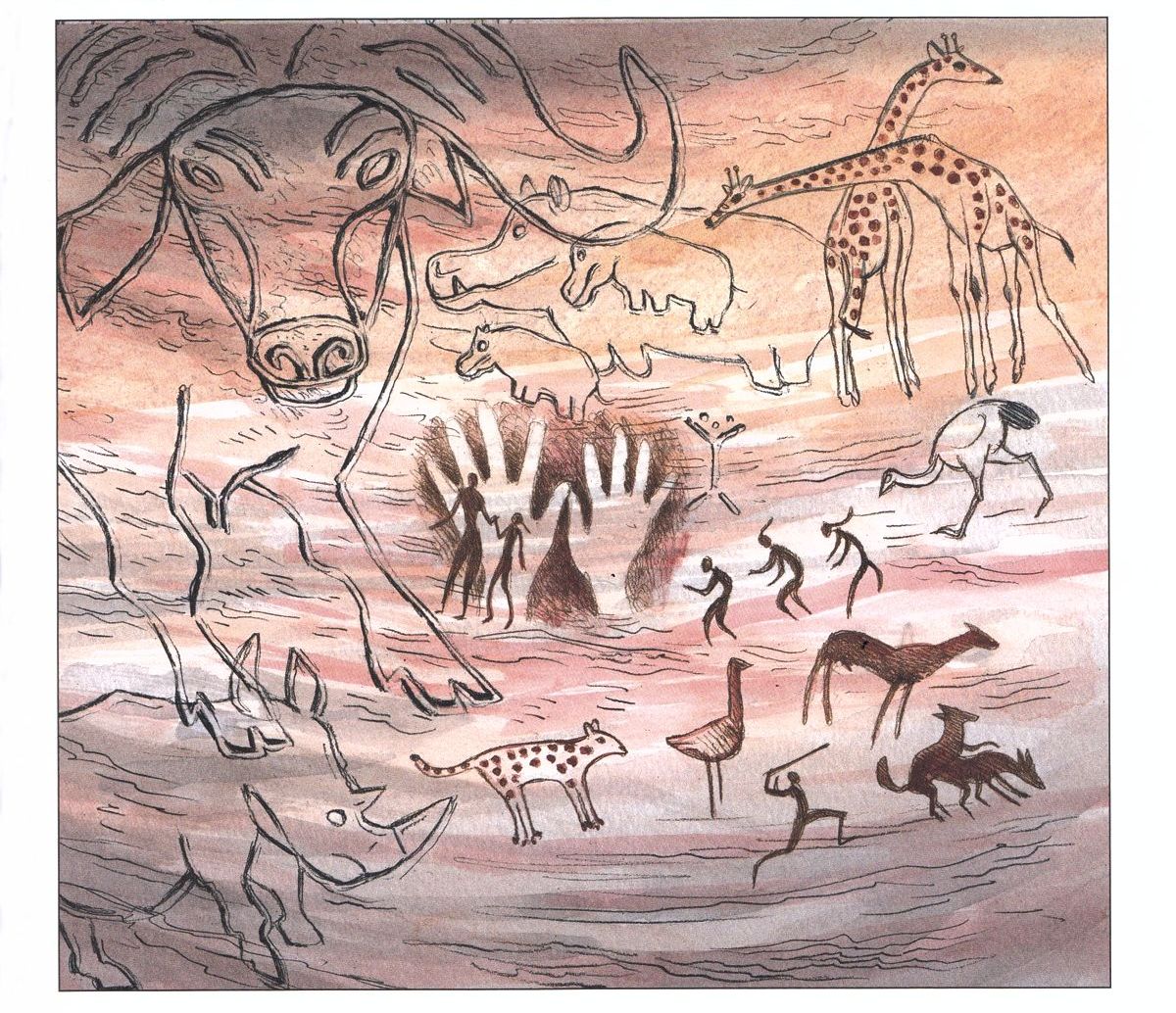

Prior to a lecture given by Jean-Loïc Le Quellec giving us a rough idea of the time frame in which the engravings and rock paintings in the Central Sahara were done, Xavier Davan, alias Maadiar, came to present and autograph « Tassili, une femme libre au Néolithique » illustrated by Frédérique Rich, also known as Fréwé. From the outset, he made it quite clear that their story was made up and was not supposed to reveal what really happened when the rock paintings at Tassali were done.

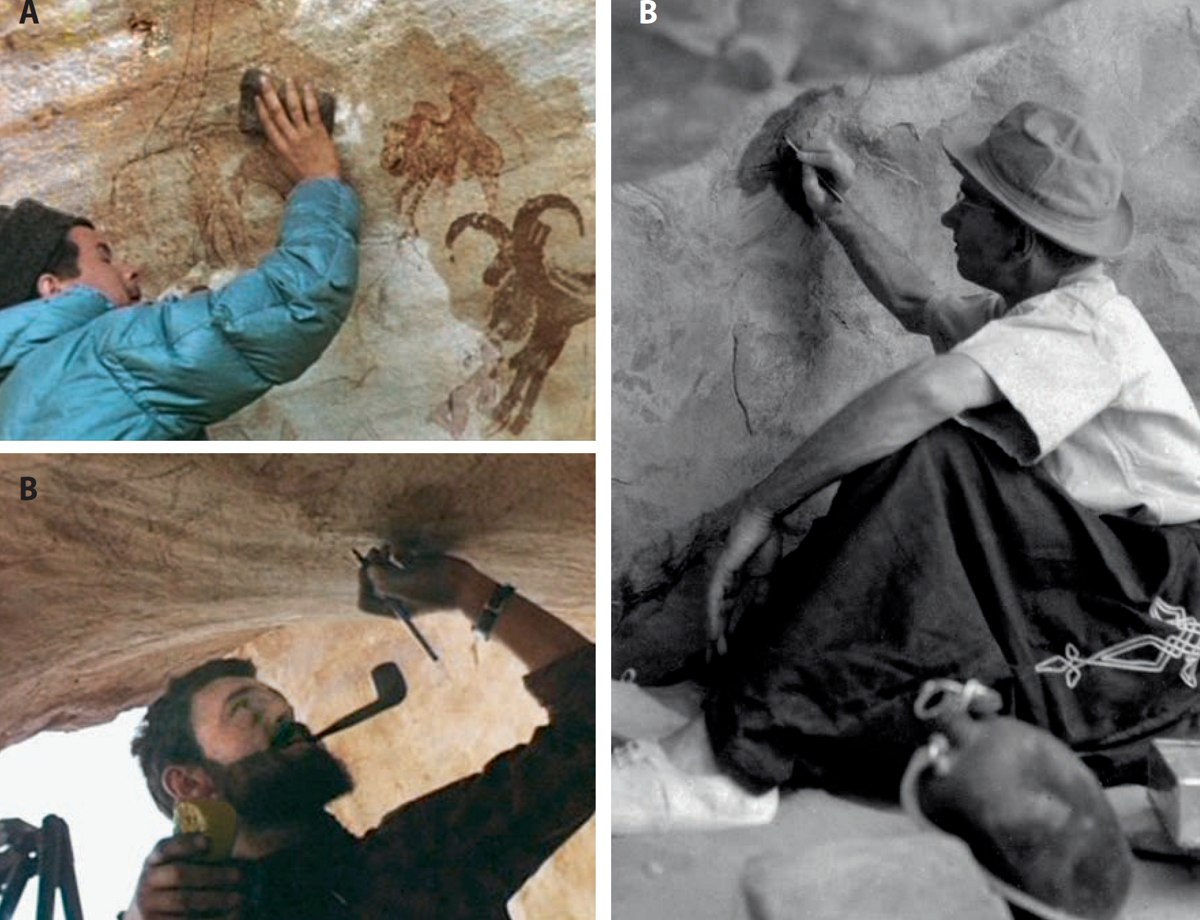

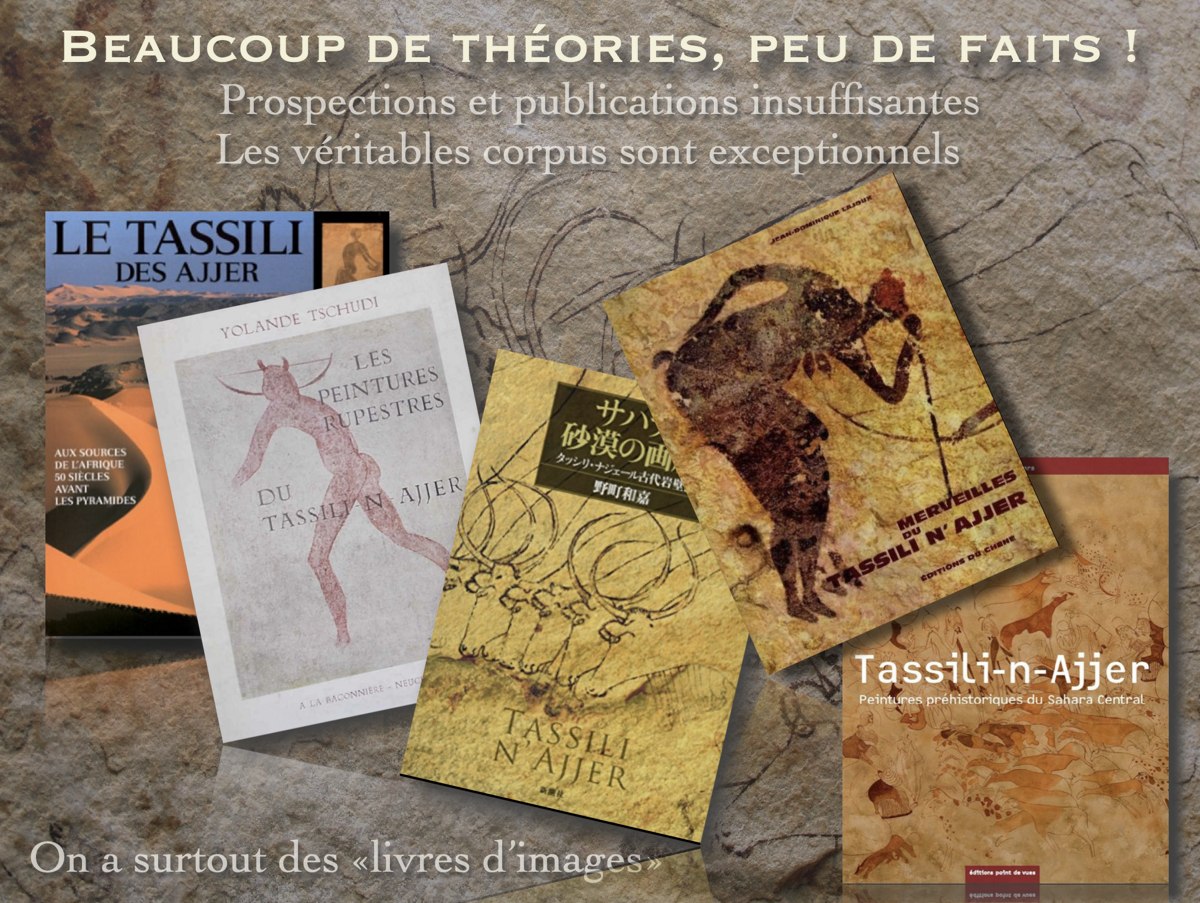

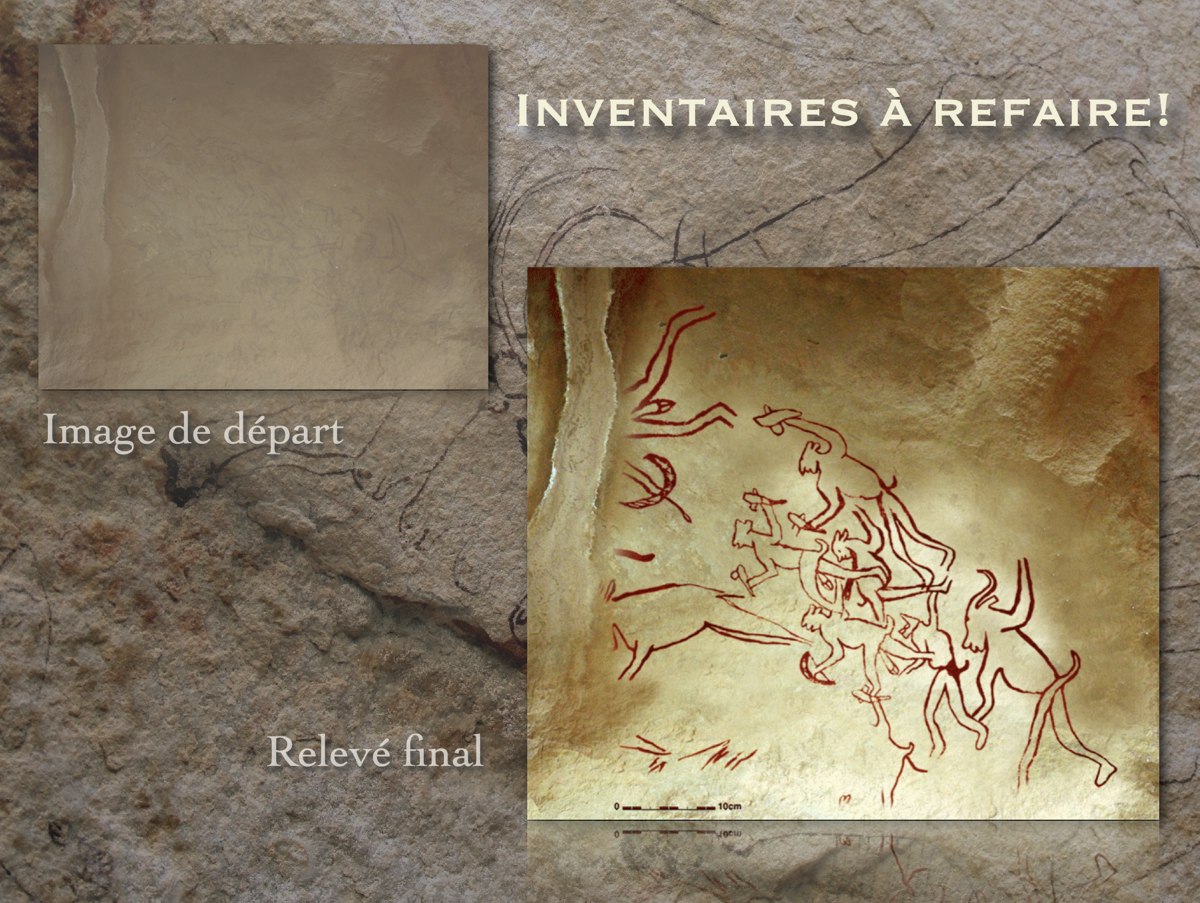

A chance to appreciate the writing and drawing skills of two free and talented artists while enjoying the opportunity to learn more about the works of art that paint a precious picture of a civilisation and that have been published over and over again since they were discovered around 1930. Undeniably beautiful picture books, but not put into context. Who, when, where? The veil is lifted. As for “why” – there will never be an answer. So we are all free to have our own way of looking at things, with no need to justify it.