MODERN ART AND PREHISTORY

IMPRESSIONS AND EMOTIONS

a survey by Sophie Cattoire

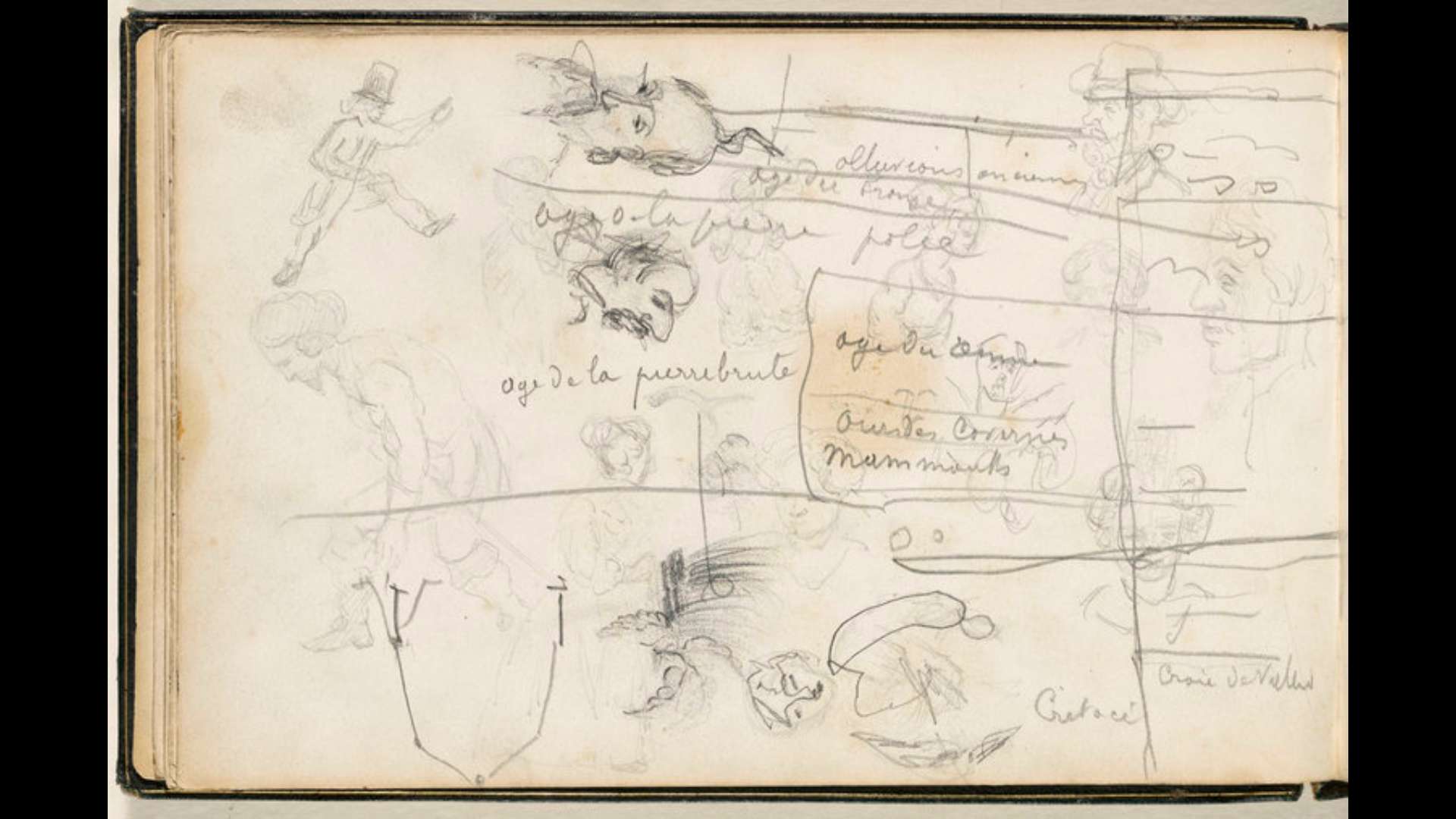

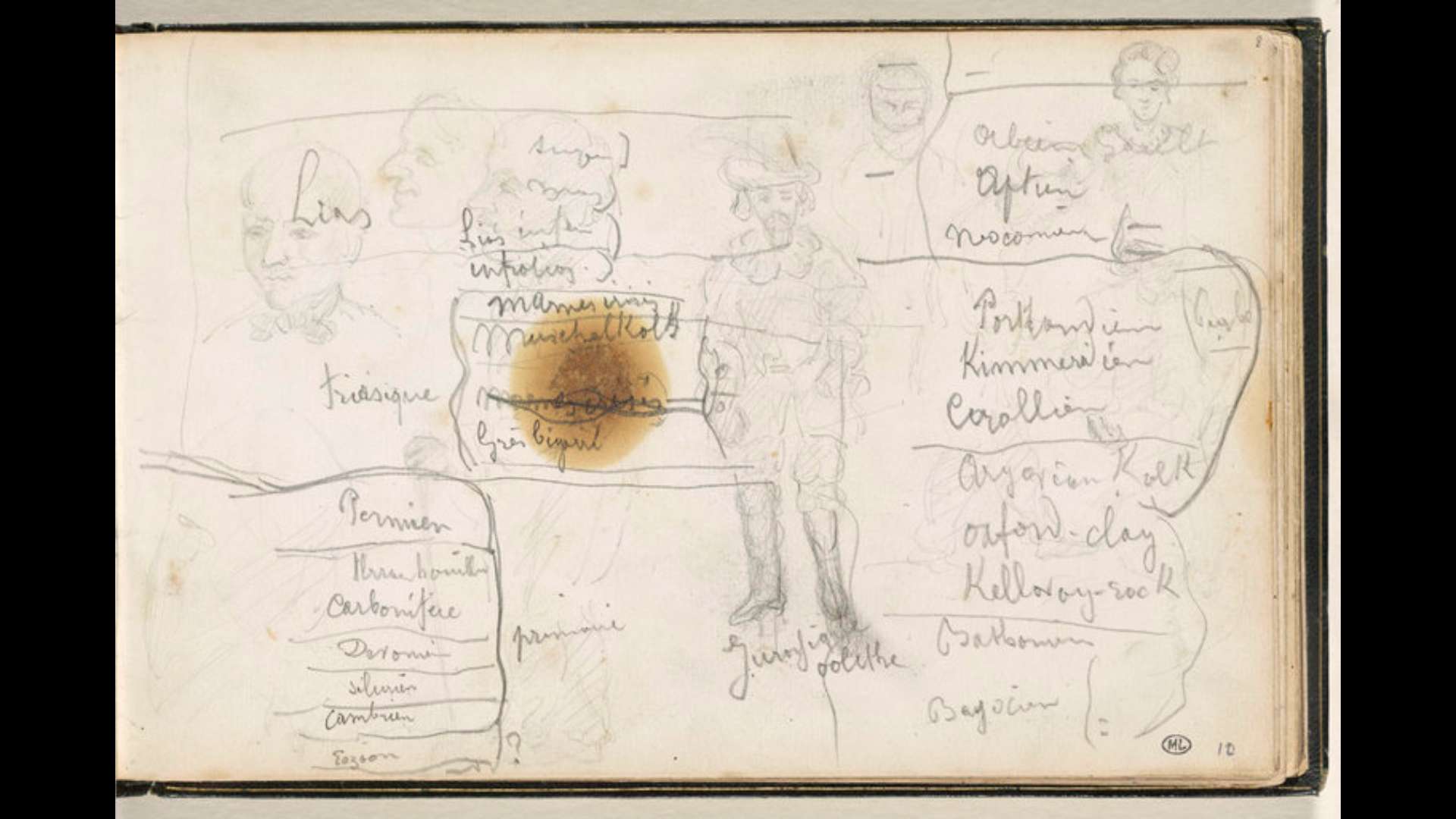

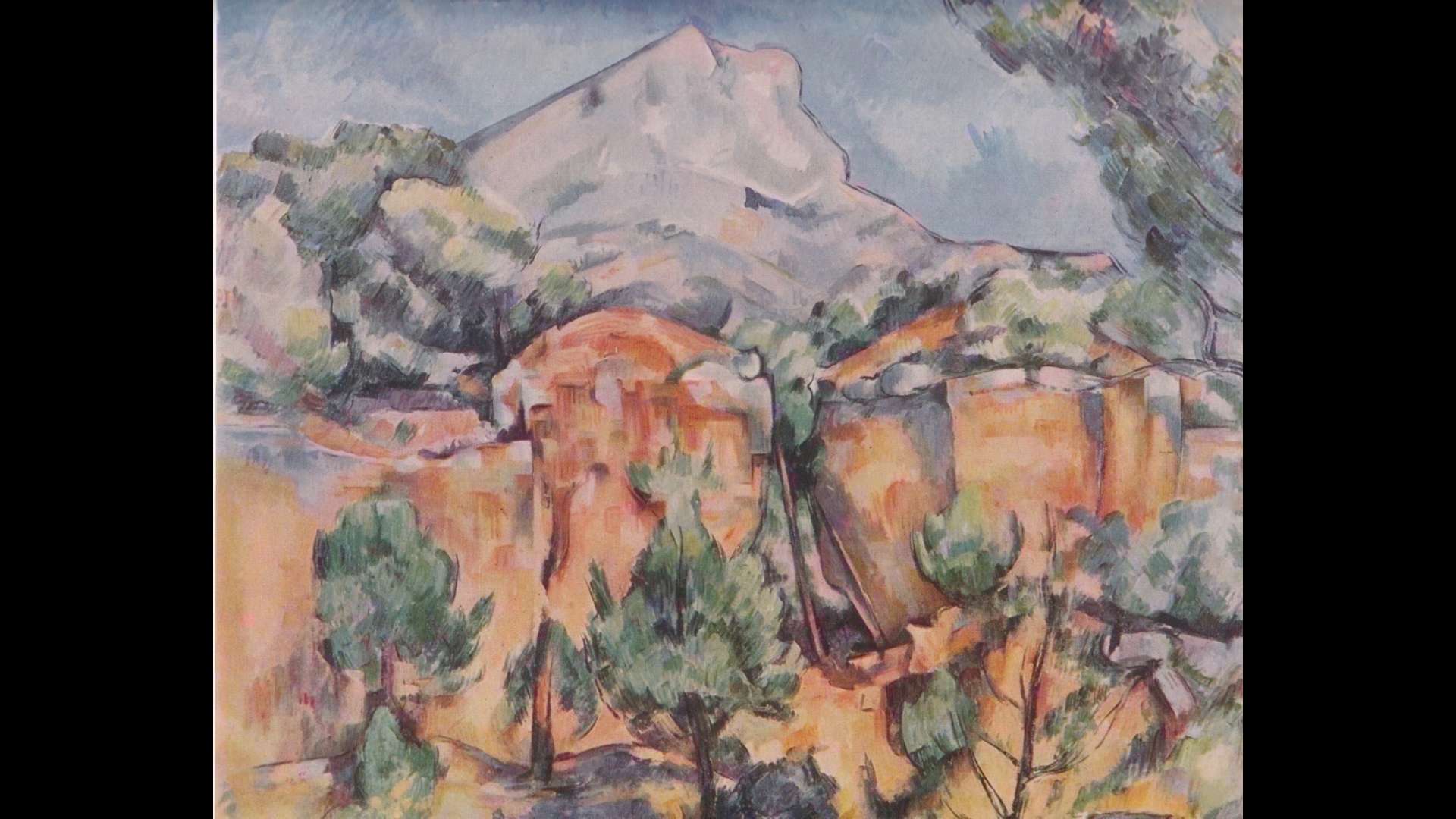

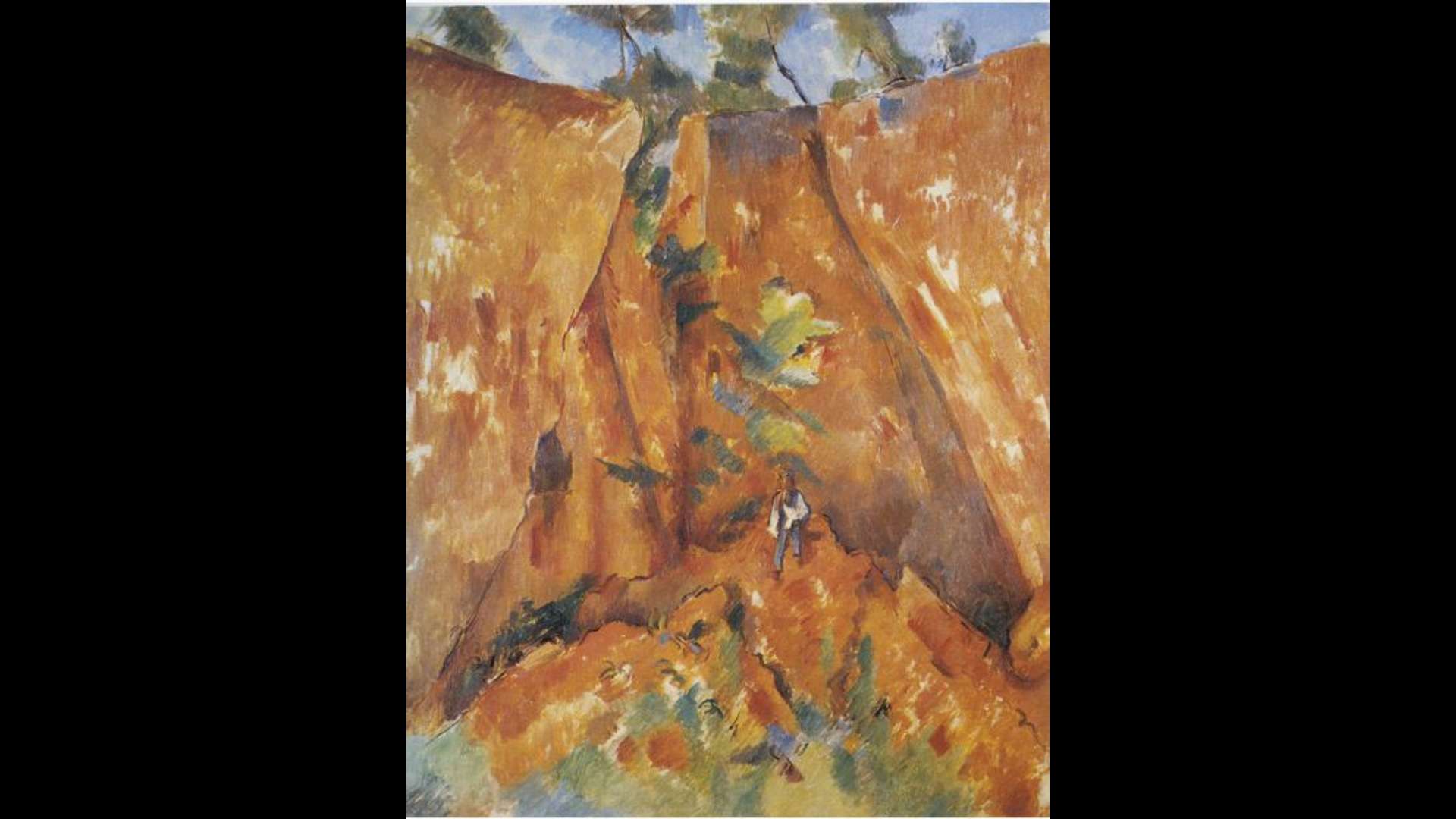

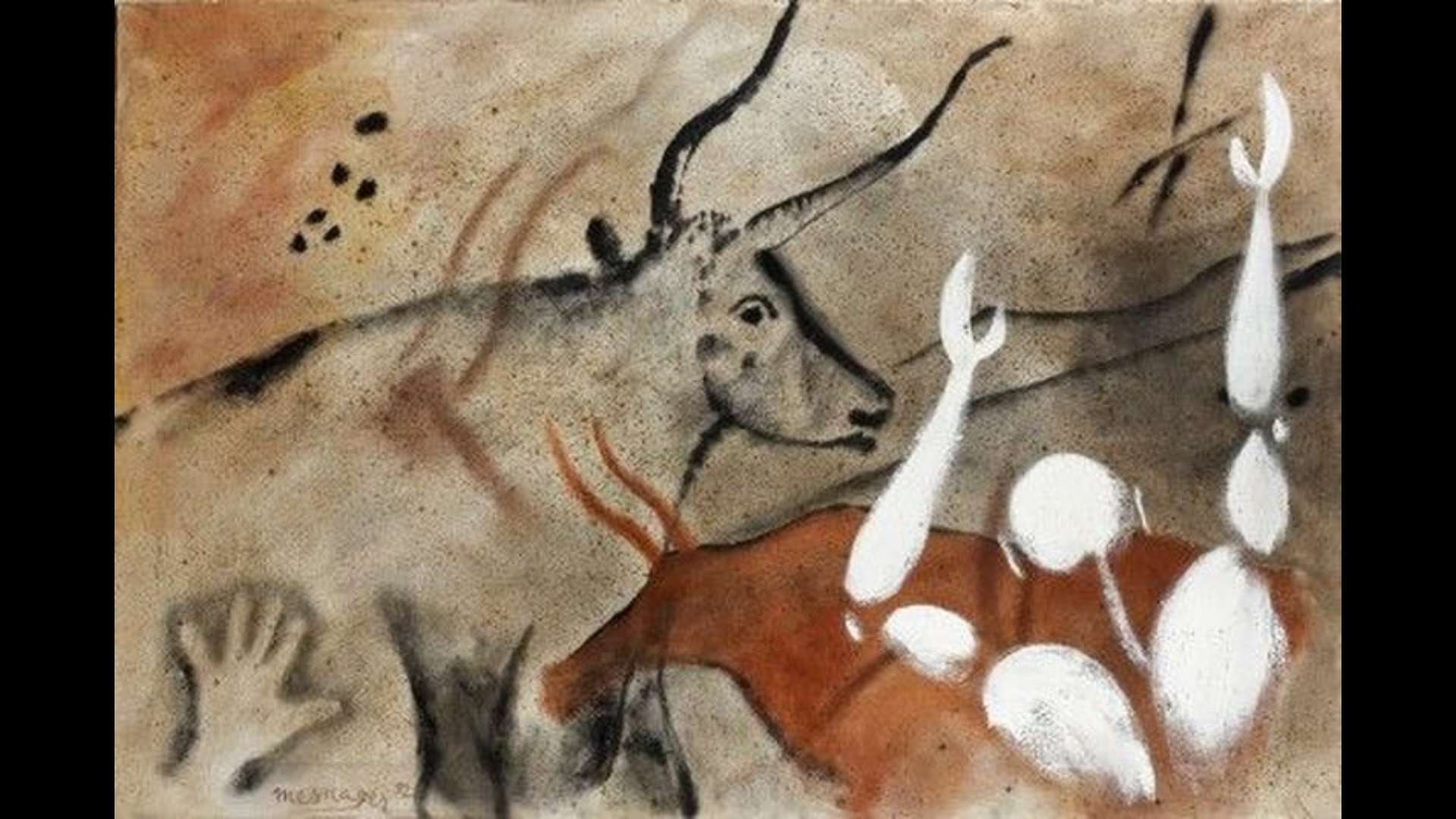

When Prehistory burst onto the scene in the middle of the 19ᵗʰ century there was a huge collective shock. No, the world had not been created in seven days; it was obviously too short a time. From that day on, Prehistory began to have a profound and confusing impact on modern man. Modern art has sometimes “translated” this shock, since artists express things they are obsessed by instead of bottling up their emotions. That is the road of research that Rémi Labrousse, modern art historian, embarked on. Last autumn he invited us to share the fruits of his research during a lecture he gave at the Pôle d'Interprétation de la Préhistoire in Les Eyzies: a follow-up to the group exhibition entitled “Préhistoire, une Énigme Moderne” held last summer at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. According to him, modern art, deeply affected by prehistoric art, reveals a sensitivity to this rich past, unlike History, reversing any linear vision of progress and imposing the idea of a loop, and therefore infinity. You can’t put a date to art. It just IS.